Steinway was founded in Manhatten in 1853 by German piano builder Heinrich Engelhard Steinway (later Steinway). The company became very successful in the US, registering hundreds of patents and defining the sound and construction of modern pianos. In 1880, in order to reach European customers who wanted Steinway pianos and to avoid high import taxes, a factory was established in Hamburg Germany. Today that factory employs around 400 people and produces 1000 grand pianos and 200 upright pianos per year, which is matched by the New York factory.

Steinway pianos have become so influential that over 95 per cent of concert halls use Steinway pianos, and that critics have said the monopoly they have on the industry has stifled innovation and led to the homogenisation of the sound favoured by pianists. As the brand edges towards production of their 610,000th piano, I'm sure the criticism won't bother them that much.

A steinway piano takes around a year to build, and contains around 12,000 pieces. Once the construction is finished, the piano is tuned using measuring instruments, before being "voiced" - given it's unique character - something that only a human can do. At Steinway in Germany this is done by Wiebke Wunstorf, who has worked at Steinway for 39 years.

"Using a tiny file, hammers and rubber blocks, she and her team of three make minuscule adjustments to ensure the instrument sounds like a Steinway. “This is something you cannot describe – it is something you feel,” she says. “You also have to learn when to stop, as it’s important to keep the power and strength of the tones. If you work too long you can destroy something beautiful – it becomes too even, and loses its character and individuality.”"*

A classic Steinway will set you back around $195,000.

*Quoted from original article, written by Mandi Keighran, featured in Qatar Airways' Oryx Magazine June 2018. Read the article after the pictures.

The Music Makers

Text by Mandi Keighran

A dozen workers sit in a large workshop in a factory on the outskirts of Hamburg, each completely absorbed in work. One holds a small flame to a delicate timber mechanism, coaxing the wood into a precise position. Another uses a mirror to work on an intricate assembly of keys, hammers, dampers and dozens of other parts. This is the action assembly room at Steinway & Sons’ Hamburg factory, and the piano builders are quietly engaged in the intimidating task of putting together the 7,000 tiny pieces that make up the action of a grand piano. Every now and then, a cluster of piano notes breaks the silence. “It takes three days to assemble everything and is very comprehensive work,” says Sabine Höpermann, the brand’s communications manager. “They work only with their hands, their eyes, and their experience.”

If you’ve ever been to a concert hall, listened to the radio, or watched a pianist perform on television, chances are you’ve heard a Steinway piano – over 95 per cent of concert halls worldwide use Steinway grand pianos; John Lennon composedImagine on a Steinway upright; and the most gifted pianists alive today – from classical virtuosos like Lang Lang and Yuja Wang to pop icons Harry Connick Jr and Billy Joel – are Steinway Artists, performing only on Steinway pianos.

Since 1850, the company has filed 127 revolutionary patents – many of which are framed on the factory walls – and is largely responsible for the piano as we know it today. It still builds each grand piano in its factories in Hamburg, Germany, and New York, using 80 per cent handcraft. In the Hamburg factory alone, there are 299 workers, 100 staff in administration and 19 trainees – together creating around 1,000 grand pianos and 200 upright pianos annually, which is matched by the New York factory. Suffice to say, the brand has come a long way since the first grand piano was built in founder Heinrich Steinweg’s kitchen in 1836, in the small German town of Seesen.

After producing 482 pianos in Germany, Steinweg moved to New York with his family in 1850. He Americanised his name to Henry Steinway, and founded his eponymous company in 1853, some 17 years after building the “kitchen piano”, which is currently on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. In 1880, his sons William and CF Theodore opened a second factory in Hamburg to cater to the quickly growing European market. Today, the brand has made more than 608,000 pianos in Hamburg and New York, each one marked with a hand- painted serial number. “Our founder’s vision was to build the best piano possible,” says Höpermann.

It all starts with the timber – maple and mahogany for the rim, Sitka spruce for the soundboard, and rich walnut, mango, olive and other exotic woods for special veneers – all carefully stacked in a huge lumber yard to reduce humidity to 15 per cent. After two years, it is put into a climate-controlled facility for three to six weeks. Then the selection begins – only 45 per cent of the vast quantity of timber here will make it through the rigorous quality control, and an astonishing 90 per cent of the Sitka spruce used to craft the soundboards is rejected due to knots, uneven grain, and other tiny imperfections in the timber.

Only then does the year-long process of building a Steinway & Sons grand piano actually begin. The rim – the outside shell of the piano – is the first step. Each enormous piece comprises up to 20 layers of timber, which are coated in glue before being fixed to a press via a system of pulleys and steampunk-style machinery that was invented by CF Theodore Steinway in 1880. “We build our instruments from the outside in,” says Höpermann. “The rim is the basis and all other parts are put in under pressure to create the best sound.” Each formed rim remains in a conditioning room – at 29°C and 45 per cent humidity – for around 100 days.

Each step is just as considered and involved – from the specially designed CNC machines that precisely cut bridges and other components to the stringing of each instrument. In one room, sanding machines roar as workmen refine the formed rims; in another, enormous 150kg iron plates hang from chains like carcasses in an abattoir, awaiting finishing by men in gumboots and white aprons, dripping with the red ink that assists with the polishing process. Often referred to as the “backbone” of a grand piano, this plate absorbs the incredible 20 tonnes of string tension produced when the instrument is played.

The soundboard department is the quietest room in the factory – a small space stacked with pristine boards of spruce. “The soundboard is the soul of the instrument,” says Höpermann. “It has to be perfect.” Muffled bangs emerge from behind a closed door as a team forms the soundboard and attaches the bridge – the only secret in the creation of a Steinway.

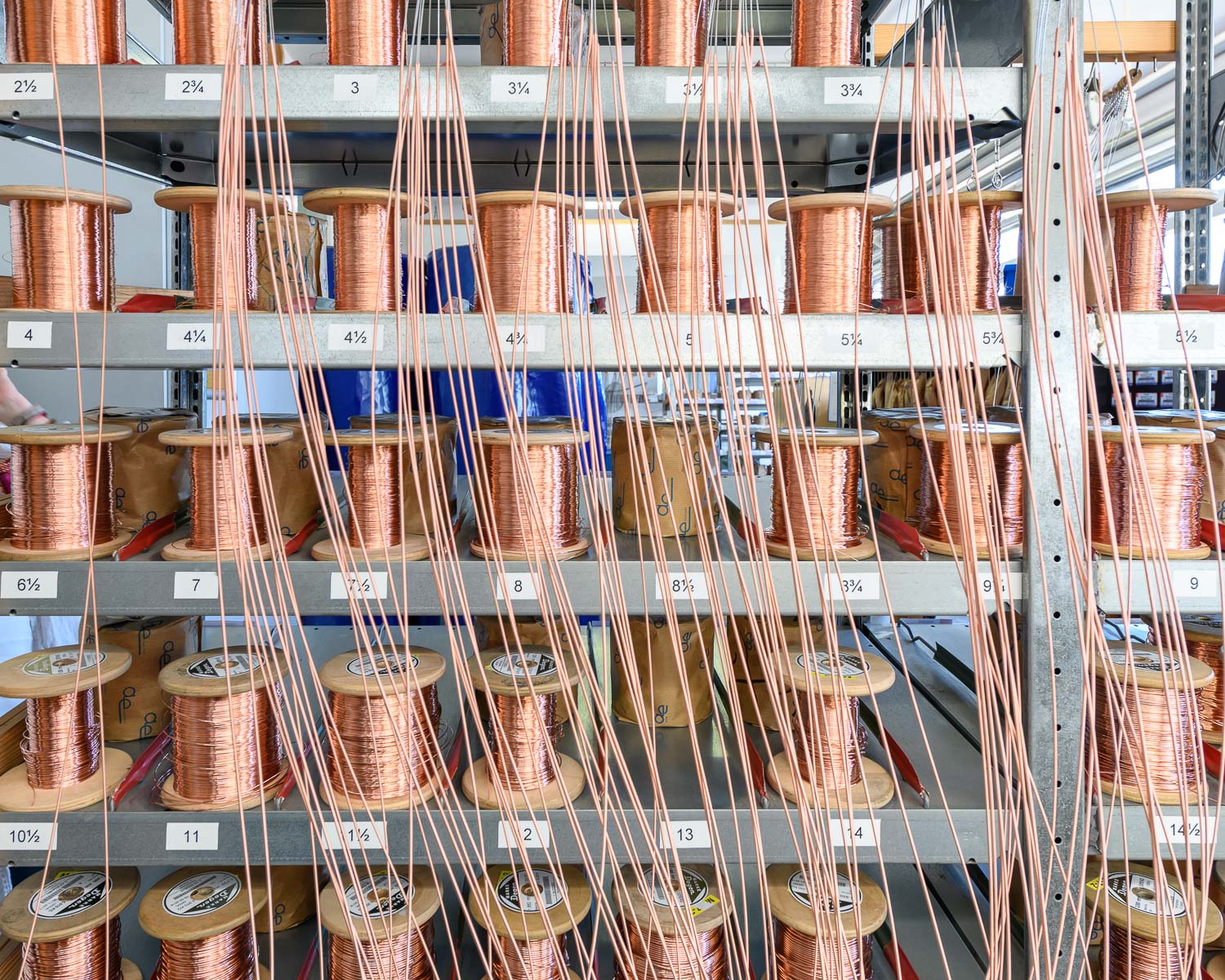

Even the copper-coated strings are made in the Hamburg factory, on a giant spinning contraption operated by a foot-pedal. Only the iron plates, the keys and the action parts are crafted in other factories – two of which are also owned by Steinway & Sons.

Once the 12,000-piece instrument is assembled, it undergoes three rounds of tuning and a final “voicing”. “The tuning is something that can be measured, using tuning instruments to create the correct frequency,” says Höpermann. “The voicing is the creation of the sound character, and is something very individual that you cannot measure.”

We visit the voicing studio and meet Wiebke Wunstorf, the chief voicer, who has worked at Steinway for 39 years. Using a tiny file, hammers and rubber blocks, she and her team of three make minuscule adjustments to ensure the instrument sounds like a Steinway. “This is something you cannot describe – it is something you feel,” she says. “You also have to learn when to stop, as it’s important to keep the power and strength of the tones. If you work too long you can destroy something beautiful – it becomes too even, and loses its character and individuality.”

The final stage of our tour is a visit to the neighbouring showroom. Here, we see the finished pianos, all the more impressive for the knowledge of what lies beneath the shining lacquer. We sit in front of a Model B grand piano, and Chinese superstar Lang Lang performs Liszt’s Liebesträumefor us. Well, kind of...

It’s a demonstration of Steinway’s latest technology, Spirio. Launched in 2016, it turns Steinway pianos into 21st-century pianolas, using a software-controlled solenoid (electro-magnetic) system to activate the notes. It’s the most advanced self-playing piano around, and offers an experience akin to having the world’s best pianists play live for you. Each note is played exactly the way Lang Lang played it when recording for the Spirio, and it’s an exhilarating experience to watch the piano play itself as if the classical superstar himself were hitting the keys.

The showroom is also a place for customers to play. “Nowadays, you can buy everything you need online. With a Steinway, though, the touch and feel is so important,” says Höpermann. “It’s all about connection.” In other words, it’s vital that you play the instrument before you buy it – especially, when you’re spending up to €159,790 (U$195,100) on a classic piano. Special orders are priced individually; the most expensive piano produced by Steinway is the €1.2 million Sound of Harmony that took four years to create. “The Steinway is a very powerful and spiritual instrument. Other brands now use our patents, but never will they be able to create a Steinway.”