Lübeck is the town of Marzipan, traditionally the confection of choice of kings and queens. The story in Lübeck goes that marzipan was invented in Lübeck when it was under siege, and all the food had run out except for almonds and sugar. Several other cities in Europe and Persia have also laid claim to inventing marzipan for similar reasons, but we'll ignore them for now.

The most famous producer in Lübeck is Niederegger, founded in 1806. I visited the factory for N by Norwegian magazine when it was in full swing for Christmas production, it's busiest time of year. The marzipan really does start off as raw almonds (usually from Spain), and Niederegger prides itself on the very low sugar content of it's marzipan compared to other producers - it believes it's raw ingredients are of such high quality that they do not need interfering with.

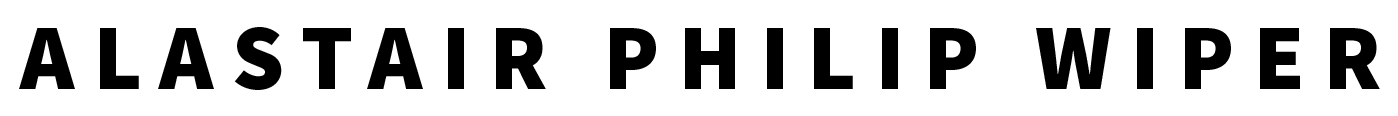

In Germany and Scandinavia, Christmas marzipan pigs are a big thing - at Niederegger they are hand painted, along with with a load of other festive characters. Scroll down for the original article to find out more.

SANTA'S FAVOURITE

Text by Sarah Warwick

The air smells a lot like Christmas, even though it’s only September. As we walk into the Niederegger factory, the scent of caramelising sugar, chocolate and almonds is assaulting –but in a good way. I bet this is what Santa’s workshop smells like.

Looking around the wrapping room, where the most delicate confectionary is boxed, it’s

like Christmas has already come to this corner of northern Germany. There are great piles of iced fruit cakes stacked up on trollies, their intricate sculpted medallions peeping out through cellophane; dozens of moulded Santas who look down benignly from shelves; and tables full of filled chocolate baubles waiting to be strung into tree decorations. Even the factory’s workers help to maintain the North Pole illusion, their heads and beards shrouded in voluminous white nets that render them elf-like.

The festive vibe isn’t really surprising, considering that Niederegger produces the world’s best marzipan – and nothing says Christmas quite like marzipan. Every August, the company’s factory on the outskirts of Lübeck lays on 300 extra staff to cope with seasonal demand. And each day their giant team of elves makes and shapes around 30 tonnes of the good stuff, churning it out in more than 300 different shapes, from Santas to pigs and their famous Marzipankartoffeln (“small marzipan potatoes”).

“By September at the latest, we have to start producing for the German Christmas market,” says Kathrin Gaebel, brand spokesperson and our tour guide for today. “We can’t even take our holidays between September and December,” she continues, seeming strangely cheerful about this fact.

Maybe her cheeriness has something to do with the fact that she spends a lot of her time

in a sweet factory. There’s certainly a frisson of excitement in our group as we’re led down high, white corridors that remind one of 1971’s Willy Wonka movie. We’re heading for the heart of the factory where the basic paste is made.

Although the almond paste originally came from the East, where it appeared around 1,000 years ago, the city of Lübeck is now the undisputed world marzipan capital. No less than four brands are produced here – but Niederegger is the only one that still makes its own paste from scratch.

Its product is also universally regarded as the best, thanks to its high almond content. It seems not all marzipans are created equal. “The less sugar, the finer the quality,” explains Gaebel. While some marzipans have as much as 70 per cent, to be certified as a “Lübecker marzipan” they must contain no more than 55 per cent. Niederegger’s has just 35 per cent.

“People often think of marzipan as something you would use in baking, but this isn’t that kind of marzipan,” says Gaebel, as she leads us into the first production room. Here mediterranean almonds, including the famous Spanish Marcona variety, are poured into boiling water to remove their skins. They fall down onto a conveyor belt, where four people scan them for residual pieces of skin. “No machine is as good as people,” says Gaebel.

It’s hot work that requires deep concentration, so these workers are swapped out every two hours. It’s also noisy: the hiss and pump of the pistons; the clatter of chains; and the thump and clang of pans are a constant background companion.

In the next room, the almonds are ground up using granite milling stones, then mixed with the sugar to form a paste, which is pressed through two sets of rollers and then caramelised in steaming copper cauldrons. Portions of paste are then shovelled out by hand by a man (there are only men in this part of the factory) with a metal shovel. Gaebel jokes that they don’t have to go to the gym because each shovelful weighs 10kg. These portions of paste will remain in cool storage until they’re ready to be processed.

The machines are hypnotic to watch and we’re eager to see what happens next. Yet we can’t. “That’s where they put in the secret ingredient,” says Gaebel, pointing to the other side of a glass door, where portions of paste wait in blue barrels to be mixed with “something near to rose water... Even I don’t know what it is.”

This mysterious additive has been the same since 1806 when Mr Niederegger set up shop in downtown Lübeck. His former premises are still the company’s main presence in the city, now a Wes Anderson-esque one-stop shop for “marzi-fans” of all ages. Everything from the complex window display (when we visited, a meta version of the shop in miniature) to the characters on sale – from traditional fruits to quarter-life-size giraffes and hippos – is rendered in marzipan.

In the attic museum there are full-size human paste figures too, like the strange love-children of Madame Tussaud and Willy Wonka. Accompanying text panels tell the story of how marzipan originated in Persia (Iran), where it was considered an aphrodisiac. It first appeared in Italy back in the Middle Ages, and came to Germany via the Hanseatic trade networks. Back then it was gifted in matabanboxes (the possible source of the name), and was initially reserved for medicinal purposes. “It probably worked as people didn’t have enough food in those days,” says Gaebel. “The mixture of nutritious almonds and sugar would have revived them.”

Although its use has changed over the last seven centuries, much of the production process hasn’t. Back at the factory, the upper floor is dedicated to the hand-shaping of marzipan using basic moulds, then its painting with airbrush sprays and needlepoint accuracy by teams of workers who add in eyes, buttons and other detail with fine brushes. “All food colourings are natural,” explains Gaebel. “They’re often made from berries, tomatoes or paprika.”

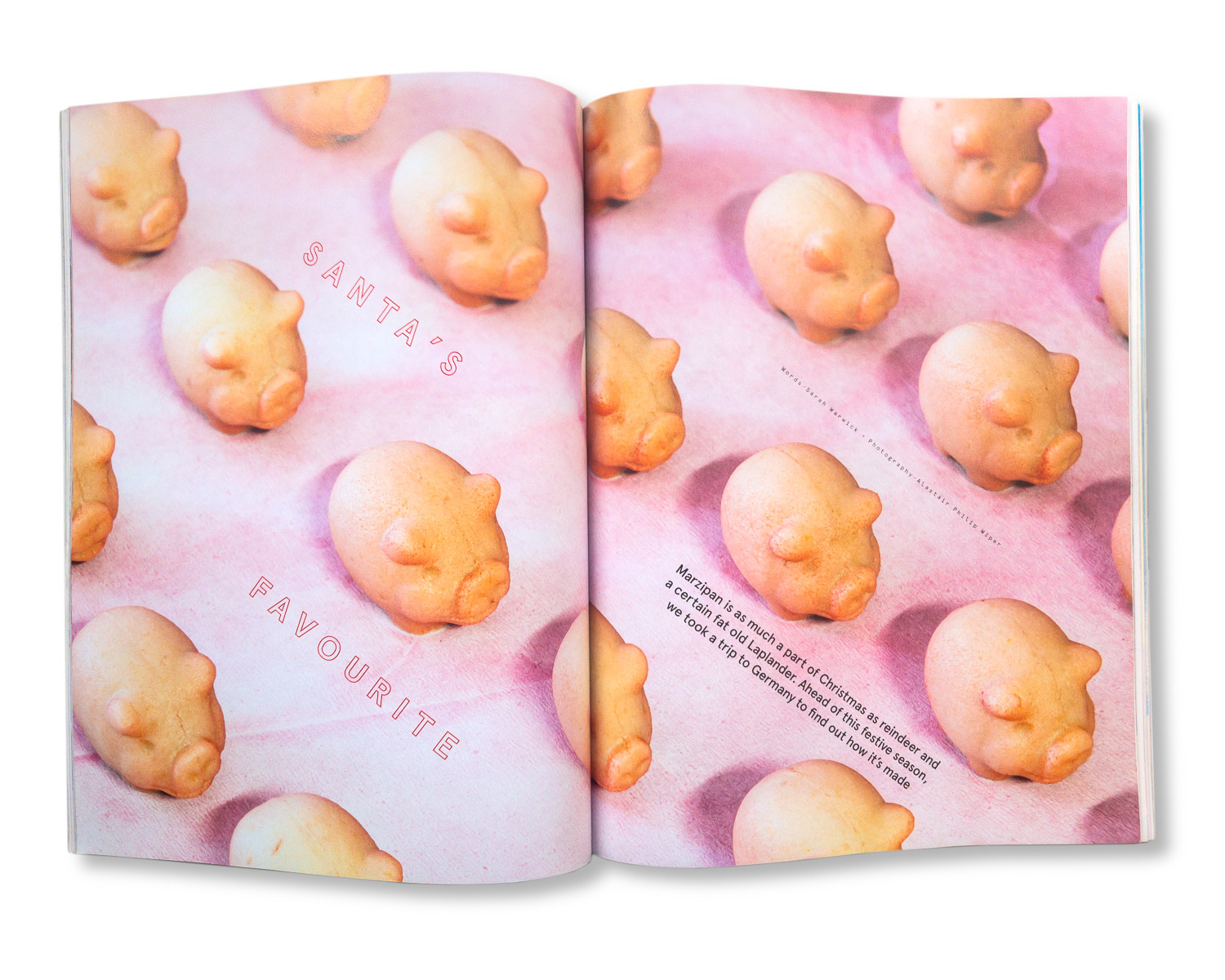

Down on the ground floor are the mechanised production lines, where all Niederegger’s “classic” chocolates are machine-shaped. It is a frankly mesmerising process. We stare on as hundreds of pieces are punched out each minute, marching like tiny white soldiers towards the waterfall of the chocolate-coating machine. They’re flipped onto their backs and land on a mat embossed with a Niederegger logo, which imprints in the chocolate.

This is crucial as, like any luxury brand, Niederegger is a target for fraud. “Recently they were selling our products in Asia but they didn’t have the logos on them,” says Gaebel. “That’s how we knew.”

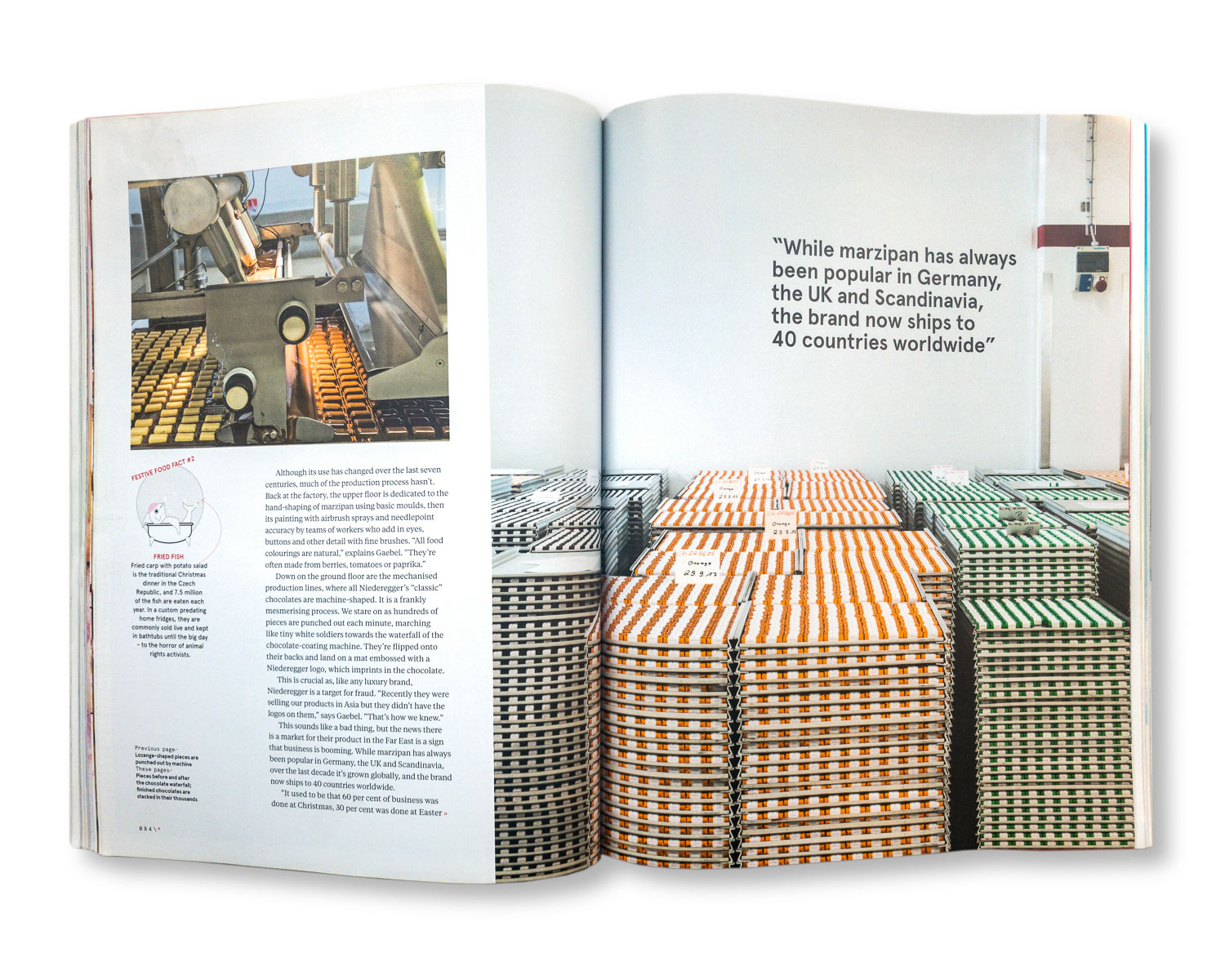

This sounds like a bad thing, but the news there is a market for their product in the Far East is a sign that business is booming. While marzipan has always been popular in Germany, the UK and Scandinavia, over the last decade it’s grown globally, and the brand now ships to 40 countries worldwide.

“It used to be that 60 per cent of business was done at Christmas, 30 per cent was done at Easter and 10 per cent the rest of the year,” says Gaebel, “but that’s changing as there are more markets and more year-round interest in the brand.”

As a result, the factory has recently been expanded and new machinery brought in. A shiny glass box takes up a good 10m-long stretch, containing a many- chrome-armed monster that bobs, weaves, folds and spins as it collates single chocolates and turns them into perfect boxes. One of its arms pecks the chocolates with bird-like accuracy, placing them in empty holes in boxes, aided by a camera in its “beak”. “Millions of euros,” says Gaebel, in response to our queries about how much it cost. We “ooh” and press our noses against the glass, suitably awed.

Overall, the Niederegger experience – my first-ever sweet factory – is as mindblowing as my child self would have hoped. We pause at the end to peel and chomp a few of today’s 100,000-strong stockpile. They come in a rainbow of colours, from plain-flavoured red to yellow pineapple and green pistachio. I was never much of a “marzifan” but I fall instantly in love with the green ones. A quick pit stop in the factory outlet on the way out guarantees I’ll have some to take home. Bet they don’t last till Christmas.