For the sake of posterity, I've decided to make this blog post about my exhibition "Avoriaz: The Enchanting Village". The pictures can be seen in various other posts on my blog, but here the actual images in the exhibition are gathered in one place, as well as a transcription of my talk at the opening with the architects of Avoriaz, Jacques Labro and Simon Cloutier, and a few pictures from the exhibition space. Well I think its quite interesting anyway, so here you go. You can catch the exhibition at Bygmingskulturens Hus, Borgegade 111 in Copenhagen until Jan 31st.

Me (APW):

Hello everybody, thanks for coming, I hope you all have a drink and are sitting comfortably. I am extremely honoured to be joined today by the architects of Avoriaz, Jacques Labro and Simon Cloutier. I will introduce them properly in a bit but first I will introduce Avoriaz and tell you a little about how this project came to be.

Some of you out there have probably visited Avoriaz, and some of you have doubtless never heard of it, so I will give you a little info about the place. I should just say I'm not an architect, and my knowledge of architecture is pretty limited at best, so I'm not going to get very technical here. I will also add that this is not an architectural photography exhibition in the conventional sense, it is the product of my imagination; I have not tried to do justice to the fantastic buildings of Avoriaz, rather I have interpreted them into a fantasy world of my own making - I'm looking forward to seeing what Jacques thinks about that.

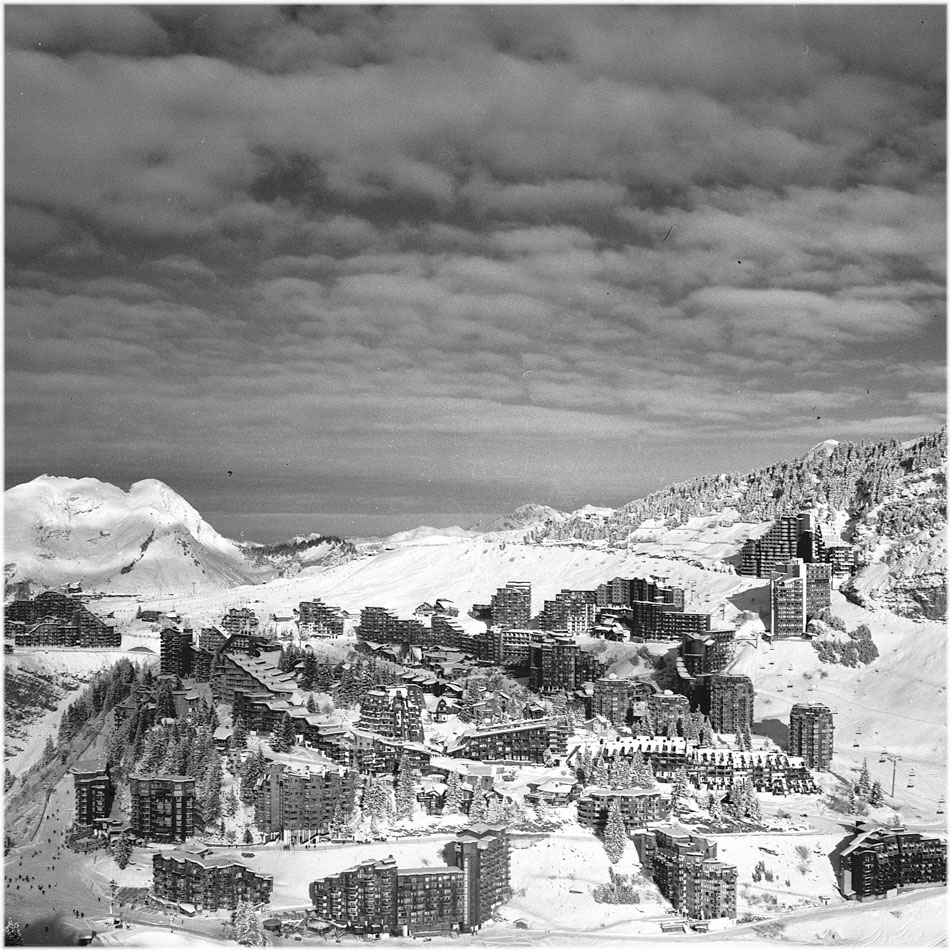

Avoriaz is a 1960s purpose built skiing resort in the French Alps, just over an hours drive from Geneva, 1800m above sea level. It is part of the Portes du Soleil ski area, a huge area that is made up of several resorts in France and Switzerland. Avoriaz started life as a desolate plateau, on a cliff high above the town of Morzine. In the summer it was used by a few goat herders, and in the winter it was not used at all, until a few brave skiers started to venture up there - the old fashioned way, walking all the way up and then skiing down very quickly. One of those energetic people was Jean Vuarnet, a child of Morzine, and winner of the 1960 Olympic mens downhill. After returning from the olympics, Morzine asked him to develop a new area for skiing around the town, and Vuarnet proposed the plateau as the site for a new purpose built resort, Avoriaz. The idea needed an investor, and Vuarnet found Gerard Bremond, son of a rich industrialist and member of the French jet-set of the 60's - I think he was in his late 20's when Avoriaz was conceived. Bremond wanted to create the "Saint Tropez de Neige" - a swinging 60's resort, with high profile guests frolicking in the snow drinking champagne. But he was also a visionary - he had a strong passion for jazz and film - and he wanted to create a totally unique resort, that embraced the modern world but was also in harmony with nature. He said:

"When one goes on holiday one hopes to find a different context to the one in which one lives daily. In Avoriaz there will be no cars. The heating will be electric, rather than fuel powered, therefore non polluting. The roads will serve as ski runs, the architecture will integrate itself into the landscape but will be new and ground breaking. It is not neccesary to explain how these proposals will cause an outcry!"

In order to fulfill his vision, Bremond hired the young, recently graduated architect Jacques Labro to assemble a team of architects and set about designing Avoriaz. In 1966, the resort opened to guests, with one hotel, the Hotel des Droments, sitting on top of the cliff. It must have been quite surreal, to say the least. The French writer, Regine Deforges, was hired to install a library at the hotel, and she explains her arrival in Avoriaz like this:

"At the time one could only access its 1800m by a swaying and squeaking cable car, which lifted one above the level of the trees. We got out relieved but with trembly legs. But what a reward! An immense white area limited only by the sky, the steep slopes cheered up by the presence of fir trees and the cliff face, a cliff like the one which plunges into the north sea or the channel. I anticipated the sound of the sea, but all around me was silence. a unique, pure silence, which made one respectful of such virgin beauty. A horse drawn carriage transported me away and the night swallowed up the mountains. "we are here" cried a voice. Looking up i saw a dark mass spotted here and there with lights, a chateau from a dark novel: it was the Hotel des Dromonts' on the eve of christmas 1966."

Bremond and Labro were successful in their vision: Avoriaz became a skiing resort like no other. When seen from afar, the buildings appear to blend in with the mountains. (show pictures) The resort is car-free, and planned so that every door opens to a piste to the bottom of town, while a series of public elevators carry people back up to the top of the town. You can ski to the shops to pick up your groceries, then take a lift back to your apartment. If you want to go from one part of town to the other, a horse drawn sleigh will take you there.

Bremond also found a great way to draw publicity to Avoriaz, by launching the "Festival international du film fantastique d'Avoriaz", a horror and fantasy film festival, which ran from 1973 to 1993. The fantastical nature of the buildings and their surroundings was the perfect backdrop to the festival, which quickly became one of the most respected film festivals in the world, and attracted directors and stars sich as David Lynch and Roman Polanski.

I first arrived in Avoriaz just after new year in 2004, and I was 23 years old. I was a ski bum - I had graduated from university a couple of years before, and been travelling since - I had spent winters in Val D'Isere in France and Whistler in Canada, and I was going to spend my third winter season in Avoriaz. I had never really heard much about Avoriaz before, and the reason I ended up there was because I had a few friends from Val D'Isere that were going to Avoriaz, so I thought I would tag along. I was immediately impressed with the architecture, a subject I knew nothing about - it was the spookiness of the buildings that really grabbed my attention. I thought they had a dark side, in a good way - and I immediately began to imagine what the architect was thinking and what he was influenced by when he was designing this place. I studied Philiosophy with Politics at university, and I don't pretend to have worked particularly hard or have been very interested much of it - but one thing that stuck in my mind was a course on the philosophy of film where we studied an old classic horror movie from 1920 called "The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari" directed by Austrian Robert Weine. I became convinced that whoever had designed these buildings had seen this film and been greatly influenced by it. I googled it later on and never found any connection, so thats one of the questions I am dying to ask Jacques about.

Avoriaz has become an important place for me - actually, if I hadn't gone there I probably wouldn't be living in Denmark today, as I met my first Danish girlfriend during that season, and followed her here, 9 years ago. My parents came to visit and also fell in love with the resort, so much so that they bought an apartment there - so I have been returning almost every year with friends and family. As the years went by I started to become more serious about photography, and Avoriaz was just an obvious place for me to photograph. I wanted to capture the fantasy that I had in my head about the place, the spookiness, the darkness, the drama. As I walked around at night I saw that the shadows really brought out the angles of the buildings and gave them the atmosphere they deserved. This series of photographs I am exhibiting today was taken both in the summer and winter, at night, and as you can see I have returned to the same position to photograph the same buildings in both seasons. Another person who was very affected by Avoriaz the first time he saw it was Simon Cloutier. Simon arrived in Avoriaz in the 80's as a ski bum, and fell in love with the architecture of Avoriaz - so much so that he decided there and then that he wanted to be an architect so that he could continue working on those buildings. At the architecture school in Grenoble , Simon made his final project about a new sector of the town, and part of that project has been realised in the new Amara area that opened last year. Simon and Jacques now work together on Avoriaz through the Atelier d'Architecture d'Avoriaz, with Simon based in Avoriaz and Jacques based in Paris.

Jacques Labro studied architecture at the distinguished École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris, and graduated in 1963. He spent a year in the US before returning and being entrusted the project of Avoriaz by Gerard Bremond, something he has spent his whole life working on, and is still developing today. In 1968 Jacques was awarded the Prix d'architecture de l'Équerre d'argent for his work on the residences of Sequoia and Melezes, and the entire resort of Avoriaz is now under protected heritage status from the French Government. Jacques has also completed works in various other skiing resorts and seaside towns in France and taught at several architecture schools in the country.

I am extremely honoured to have both Jacques and Simon here today, thank you so much for travelling all this way to be here. I'm going to ask some questions now, and then we can take some questions from the audience afterwards - Jacques doesn't speak much English, so Simon will translate for him - so please bear with us, it might go a little slowly at points but I'm sure it will all be worth it.

Alastair Philip Wiper (APW): So, I'll start with a very important question for you: do you like skiing?

Jaques Labro (JL): Yes we love it! I am not very good, but I still love it. And paragliding too.

APW: Wow, thats the one where you ski off a cliff with a parachute?

JL: Yes

APW: Its good you like skiing since you spent so much of your life in a skiing resort. I was imagining you might say that you hated it and you never wanted to see any snow again in your life.

JL: Haha no, luckily I love it.

APW: So the next question I have to ask is: Had you seen The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and was it an influence?

JL: I had seen it, but no it wasn't an influence. The mountains were more of an inspiration. And other architects of the time, Alvar Alto, Frank Lloyd Wright, Gaudi, the expressionist architects that were the base of my studies. APW: For me the buildings have a dark, fantastical side to them, and when Gerard Bremond came up with the idea of the film festival, he also saw that the buildings and the location had that atmosphere to them. Were the buildings intended to have that side to them, or was it just the nature and the mountains that inspired the aesthetic?

JL: The buildings were not intended to have this fantastical element, but when Bremond came up with the idea for the festival I thought it fitted perfectly, I could see why others thought that. Bremond is very cultured, he is very passionate about film and music. But I think that the buildings are only adding to the fantastic nature of the area, it has always been like that - the cliffs, the plateau, the fact that when we opened Avoriaz there was no road, you had to take the cable car.

Actually the whole idea of no cars was very very important to the concept of Avoriaz - it is still completely unique in the world for a skiing resort I think. It was Jean Vuarnet who pushed the idea that you had to be able to ski in and out of every building, and this was very controversial at that time because the car was king, it was almost a symbol of France. But the idea was that by parking your car at the bottom of the cliff, and then leaving the ground and flying through the air in a cable car, and arriving in a new, magical place where everything looks different, like another world, was very important when we were designing Avoriaz. You should be leaving your normal world behind and experiencing something else for a week. We even brought reindeer from Lapland to pull the sleds, to add to the magical feeling - but it ended up being a bit of a disaster because you cannot control a reindeer like a horse, they get scared very easily, so soon there was baggage strewn all over the resort by out of control reindeer. They lasted for three years and then we had to get horses instead. APW: Jacques, I think you were 31 years old when the first hotel, the Hotel des Dromonts was opened in 1966, and you had graduated less than two years before. When we had lunch earlier you told me that you had never been to the mountains at that time, let alone skiing, so can you tell me how such a young team came to be entrusted with such a huge project?

JL: I was working on a project for Gerard Bremond's father, as one of many architects, and Gerard saw a model I had made one day and thought it was interesting. So he told me about Avoriaz and we started to get on very well, and it went from there. Gerard's father was a very rich and successful industrialist who was working on some huge, huge projects, and he gave the Avoriaz project to his son as something that was not that serious, something for him to play around with. And I never knew I would keep working on Avoriaz, I never had a big contract for more than one building, we would always do a new deal for every building. Actually, the contract was usually signed after we had finished the building. The whole project at that time was really a product of its age - I think it would be impossible to do now i the same way with such young guys, there would be too many people involved, banks, regulations and so on. Back then it was just a handful of us who decided everything.

APW: I should probably just point out to the audience that Bremond founded the French tourism company "Pierres et Vacances" in Avoriaz, which went on to become the biggest holiday company in France - just about every village worth going on holiday to has a Pierre et Vacances residency. So he made a pretty good job out of his fathers little whim.

Simon also told me earlier that you and the other architects were all very interested in jazz, and that you designed the buildings in the way that musicians improvise jazz - can you tell me a bit more about that?

JL: We had a team of architects that were like a band, and one guy would be the bass player - he would do the basic drawings, lay down the foundations. Then each architect would come and "play" on top of that, have their own solo, put their own character and history on top of that. It was like improvisation, but of course we were doing drawings so its not so quick as that. We tried to be instinctive.

APW: When Avoriaz was first conceived, it was supposed to be a luxury resort for the jet set - but when I arrived in 2004 I would say it was not a luxury resort - there was only one hotel, and most of the apartments were very small and designed to fit as many people in as possible. I would say it was a skiers resort. But now, with the new developments, more luxury apartments are being built - can you explain why the resort has evolved like this?

JL: The Dromonts area was designed to be luxury, and had private apartments that were not supposed to be used every week, only when the owner or their friends were there. But of course we needed to make this a real town, the baker needed to keep his business going, so we needed to create some mass accommodation that could get people on and out, and as many as possible. That is how Bremond came up with Pierre et Vacances - the idea is that people would buy the flat, but rent it to Bremond so that he could sub-let it and make sure that every week it was full of people. And it was also about the budgets of those people at that time, in the 70's, people didn't have big budgets to go skiing, so we had to cater to them. But now there are people that want bigger apartments, there are some people with some more money, so that is what we are building now. But the architecture is the same, the people are treated equally whether the apartment is big or small.

APW: When I lived there I was lucky enough to know some guys that looked after different apartments, and I managed to get free accommodation for most of the season - but the catch was that I had to move to a new apartment every two weeks or so. But I got to live in about 10 or 12 different apartments, and visited many more - and there is one thing I remember about many of them that we all wondered about, and that was the bathroom doors - they were round, and you had to step through them, like you were on a boat or a 70's spaceship. Is there a reason for that?

JL: Actually yes, it was very important. We could only build in the summer, so we would have to get the whole building finished within a few months. so we built the shell of the building, with lots of empty boxes, and then we had the whole apartments pre-fabricated and we lifted them in with a crane. Everything was already in the apartment, kitchen, toilet etc. and it just had to be connected up and then we would put the front on the building. The doors between rooms had to be that shape because otherwise they could bend or go wonky or fall apart when we tried to lift the apartment into its box - they were there to strengthen the apartment. Now you can put in whatever door you like, it was just necessary while we were lifting it in.

APW: Simon, you have a pretty interesting story about how you came to be working in Avoriaz with Jacques. Can you tell us about it?

Simon Cloutier (SC): I came to Avoriaz in 1989 as a ski instructor, I didn't really have big plans for the rest of my life at that stage, until I saw the buildings of Avoriaz. And I thought, ok I have to become an architect so I can make buildings like this. I went to architecture school in Grenoble, and I still taught as an instructor in Avoriaz sometimes. I was in my second year, and one morning I saw the name "Labro" on my list of pupils for a snowboard lesson. I thought it was probably Jacques' brother because he is a very well known journalist in France - but no, it was Jaqcues, who was coming to have a snowboarding lesson in his 60's. During the two hour lesson Jacques didn't progress very much in snowboarding, but I progressed a lot in architecture - Jacques agreed to be my mentor, and I went on to do my diploma in the future of Avoriaz, what it would be like in 20 years. And that is what we have built now, with the new sectors of the town.

So now we work together, Jacques lives in Paris and me in Avoriaz. But Jacques know Avoriaz much better than me - if we are on the phone and I am looking at a location, he will say "look over there and you will see this view" and I don't agree - but I will look and he will be right, he knows it exactly.

APW: Ok this is going to be my last question. How do you see Avoriaz in 50 years?

JL: Avoriaz is less than 50 years old, so it is very young for a town. If it is double the size in 50 years, it will not be the same - it will not be a walking resort, because the distances will be too big. And it is limited by the nature, the plateau, the cliffs. I am thinking of a development, in my head it is ready, it will be more like a satellite town with a connection to Avoriaz - not too close to be joined, but not too far to not be able to participate with Avoriaz. Perhaps they will be linked with a cable car or something.

I think the work we have done in Avoriaz is just as much town planning as it is architecture - we have thought very hard all the time about linking the buildings together and making every area accessible by foot - it is important that the people that visit Avoriaz get out and see the town, participate with it. The architecture and the urbanism is driven by the landscape - in the area in front of the cliffs you can place big buildings because you have the cliff behind it, so they don't seem so big, and in another part of town on the small hill we have smaller buildings. And then on top of the cliff you can also put big buildings as they blend in with the skyline. The Romans talked about "genius loci", understanding the genius of the landscape that is there already and working with it.