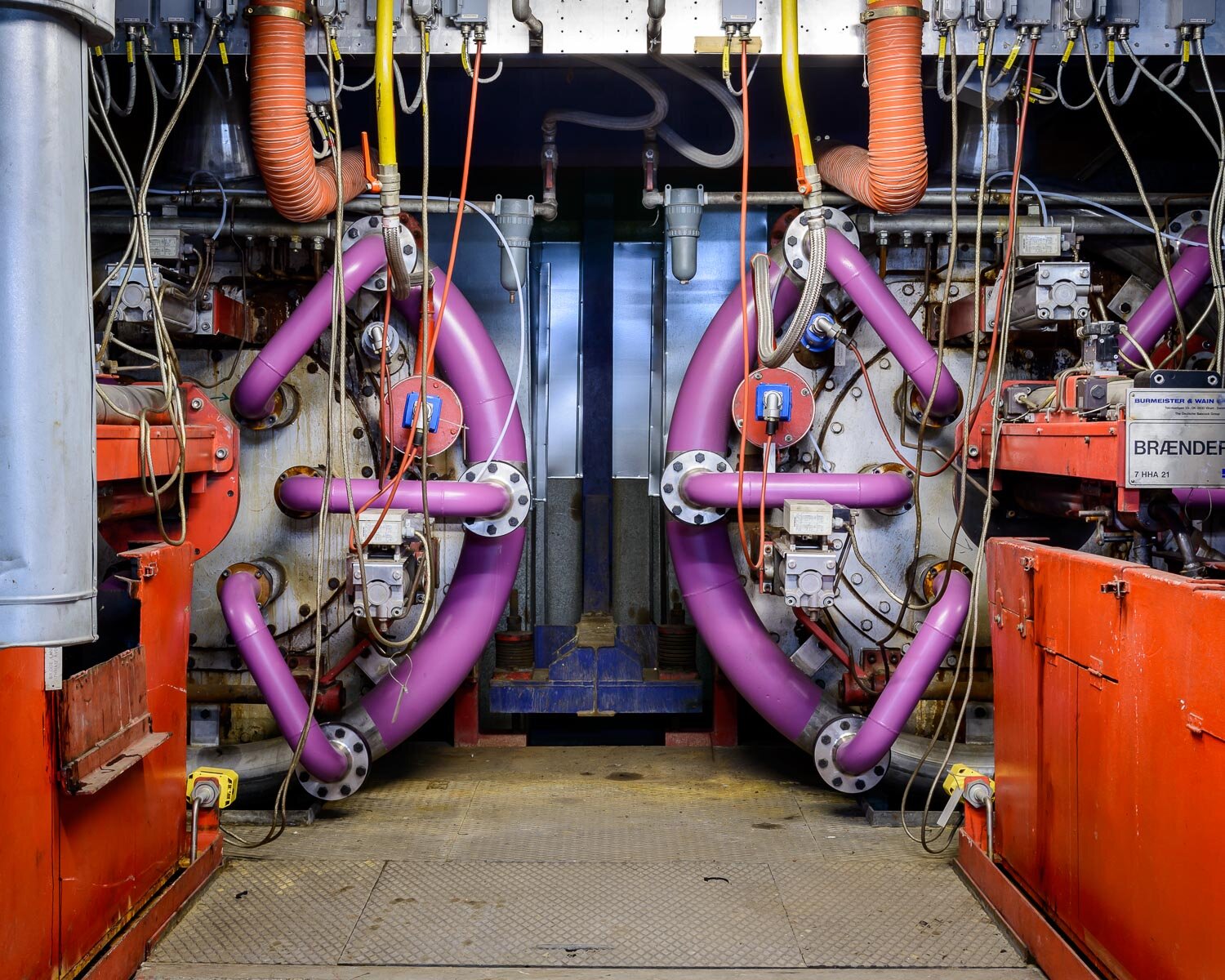

UNINTENDED BEAUTY

ALASTAIR PHILIP WIPER

There is nothing in machinery, there is nothing in embankments and railways and iron bridges and engineering devices to oblige them to be ugly. Ugliness is the measure of imperfection.

- HG Wells

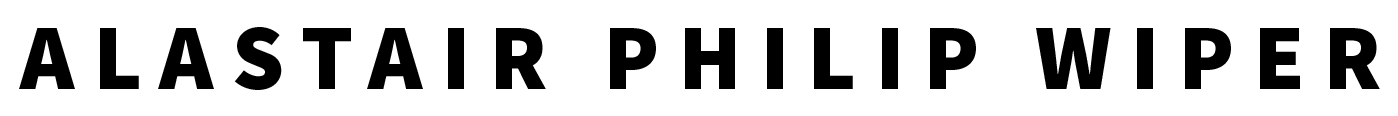

Unintended Beauty is an exploration of the accidental aesthetics of industry and science by photographer Alastair Philip Wiper. The project explores a range of contemporary scientific and manufacturing sites, spanning from facilities tied to material production like Adidas shoe factories, to the particle beams colliding at the core of the ATLAS detector at CERN, and extending to food processing facilities like the slaughterhouses of the Danish Crown company. The images offer a rare insight into workplaces that are usually kept behind closed doors and reveal these infrastructures' hidden beauty and incredible complexity. Machines that smash atoms together, make fabrics or stuff sausages all result from human collaborative imagination and tell us about who we are: our needs, desires, madness and our vision of the future.

The sustainability of this future depends on our ability to create and innovate. The exponential creativity associated with cutting-edge technology strongly contributes to our well-being and, at the same time, represents a threat to life on earth. These aesthetically fascinating photographs give insight into the heart of the design process and question our production methods and the scale of that production.

British photographer Alastair Philip Wiper (b. 1980) is known for his unique ability to portray subjects of industry, science and architecture. Alastair’s signature is defined by an understanding of lines and symmetry, colour and contrast, often combined with dark humour. His prints are included in the permanent collections of institutions such as the Design Museum in London and the Royal Institute of British Architects, and he has produced several books, including Building Stories (2023), Unintended Beauty (2020) and The Art of Impossible (2015).

The project was produced around the world over an 8-year period, and includes the facilities of companies and institutions such as CERN, adidas, Boeing, The European Space Agency, Steinway & Sons, Bang & Olufsen, Playmobil and many more.

IMAGES IN THE EXHIBITION:

BOOK

208 pages, published by Hatje Cantz 2020. More info here.

INSTALLATION

Unintended Beauty at Kvadrat, Copenhagen, Denmark, 2021:

Unintended Beauty at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs et du Design (MADD), Bordeaux, France, 2020:

Unintended Beauty at Les Champs Libres, Rennes, France, 2023:

INTERVIEW

Interview with Alastair Philip Wiper by Ian Chillag, host and creator of Everything is Alive, an award-winning podcast in which he interviews inanimate objects about their lives.

Ian:

It's been such a pleasure to look at these images. One thing that happens is, I look at one and I think, "Wow." And then I think, "What? How can this be what this is?" And I wonder how often you had that feeling when you were actually in the space. If you gave me a thousand guesses of what the image from the Playmobil factory actually was, I would never guess that it was making tiny Playmobil figurines.

Alastair:

Well, that's good because that's what I want to achieve. The goal is to make people look twice. I want them to have an immediate reaction to the picture where they think, "Wow. What is that? I need to look closer." And then when they look closer they realize that they can't quite figure out what they're looking at, and maybe then they have to read a little bit more or wonder a little bit more about it.

Freshly stuffed salami at the Gøl sausage factory, Denmark

Ian:

There are some of the facilities where if you study the image, you can guess what is being produced. Like the Kvadrat Textile factory – you can tell something is being woven, or at the vinyl pressing plant you can tell that there's a record there. But the actual process that you're witnessing is totally new.

Alastair:

I suppose I like to try to touch upon something that represents what is happening in the place but leaves a lot of mystery as well. Not all of the questions need to be answered.

Ian:

When you subtract what is happening from these images they're still compelling. You can study them aesthetically, free from what they're actually producing. Do you think about the contrast between how the facility feels and how the product that results from it feels? For instance I think about the photograph of the Absolut Vodka Distillery, and there is nothing about that makes me want to drink vodka. It feels very industrial. It looks almost like a chemical processing plant, which I guess it is, or like a rocket launch pad, and it seems so far from the experience of sitting down and drinking a vodka martini.

Alastair:

I think that contrast is particularly apparent in the places where food and drink is produced on a large scale. People imagine that their shoes are made in a factory in Asia, so they don't get a huge surprise when they see a lot of people making shoes in a factory in Asia. But when they see the pigs being turned into sausages there's a big disconnect between what is on their plate, which people have a very personal relationship to, and this big industrial process that goes into producing their food, which is almost the same as in any other factory. A lot of people don’t want to think about that, even though their imaginations of what happens is often worse than reality.

And to be honest, I don't think it even matters that much what it is that the product is, if it's something that you're going to be eating or drinking. I've had a lot of people assuming that the meat plants that I've been to are particularly gruesome, but I’m sure that if I went to a plant where they made vegetarian lasagna on an industrial scale, it wouldn’t be very appealing. So, putting the controversial animal aspect of meat production to one side, I don't think any food is appetizing when you see it produced on such a large scale.

The real issue for me is that we need to eat – and produce – such a huge amount of meat, which seems totally unnecessary. I guess you could say that about most of the things we consume these days.

adidas shoe factory, Indonesia

Ian:

I was also struck with the image of the slaughterhouse with the pigs hanging from the ceiling, how ordered and clean it was. That was nothing like I expected. The pigs, which are organic things, look like they could have been produced at a factory that was making identical pigs. A pig-stamping plant.

Alastair:

Well, actually that was definitely the nicest looking part of the slaughterhouse, so I'm not trying to pull the wool over your eyes and convince people that the whole place is like this, because there is a point where they also take out all the guts and it gets pretty bloody.

Plywood mock-up of part of the ATLAS Detector, CERN, Switzerland

Ian:

You seem to be drawing an echo in the book between the slaughterhouse image and the Realdoll sex-doll factory, where the dolls are hanging very similarly from the ceiling. I think there are echoes like that throughout the book which are interesting. All these products that are being made and processed are very different, but at a factory level there are weird things in common between, say, how a piano is made and how a Playmobil figure is made and how a huge salami is made.

Alastair:

That's true. When I get into these industrial spaces I'm drawn to the sense of repetition – it is something I'm conscious of trying to show when I'm there. There’s something graphically interesting about the production line, and the story of things moving along through a process.

Ian:

I imagine the raw materials are probably similar between an Adidas shoe and a sex robot, and it's through the processes that you're witnessing and photographing that they become these entirely different things. It's not unlike human beings, who are made of all the same raw material but end up living completely different lives and becoming completely different creatures.

Alastair:

Are we that different, though? We're also quite similar when it boils down to it. We all just want sex and food. Right?

“The Octopus”, a machine that sucks plastic pellets around the factory, Playmobil, Malta

Ian:

Has the process of doing this work and spending this time witnessing the process of the creation of these things changed your attitude to and your reaction to these products in your life? Like, when you walk by a Steinway piano or an Adidas shoe, has what you've seen of how it got there changed the way you think about it?

Alastair:

Yes. This whole process has been an education for me. Having the chance to go into all of these places and see the way that things are made, I just turn into a little kid again in a lot of ways. I'm often shown around a facility by somebody who's worked there for 20 years and knows the processes inside out, or a scientist who is extremely well qualified and understands the intricacies of the experiments and the machines that they're using. I can't understand myself what is going on in a lot of these places, especially the scientific places, and I don’t expect to ever be able to really understand them properly. But getting an insight into the way these things are made and the way that they work is just fascinating, it is an utter privilege, sometimes I think I have the best job in the world.

I do spend a lot more time thinking about what a complicated world we live in, and how the products we use and the way they are made contribute to that world. With this project I’m trying to celebrate the ingenuity of humans and the way that we come together and we create these machines and we supply the needs of society – power, food, dildos - and we try to answer the questions about where we come from and what's out there in the universe and that kind of thing. I’m trying to stay as neutral as possible with the images, to give an insight and let people make up their own minds about how they feel about what they are looking at.

But it has become increasingly impossible for me not to think about where we are going as a society and what we are doing with the environment while I have been making this work, especially in the production facilities. The human ingenuity that I am celebrating with this book can also be seen as a symbol of where we are going wrong in the world, symbols of overconsumption and the negative aspects of capitalism. I’m confused about it myself - how are these facilities and products contributing to the world we're living in, what has to change, and is it going to change? And is this human ingenuity going to save us or is it going to be our downfall?

Odeillo Solar Furnace, France

Ian:

I think it's an interesting insight, and there's something very strange about the fact that many of these places are producing something, but mass production is also a kind of destruction. There is something bittersweet to celebrating that ingenuity, because every efficiency that you are photographing has a consequence.

Alastair:

Yeah, and those consequences are just becoming more and more apparent by the day. If you look at a jumbo jet, for instance - basically human beings have figured out a way to take a lot of bits of metal and put them together in a very specific way, and feed it some fuel and make it fly. And that's amazing. Seeing a jumbo jet taking off, that's part of my inspiration for this whole project. But now we're finding out that jumbo jets are really bad for the world, as is almost everything that we use. And that's a confusing place to be.

I've flown around the world quite a bit just to make this project. And there's a conflict there, which I'm trying to work out. I hope that our ingenuity and the combination of technology, political will, regulation and consumer pressure will save us and get us on the right track. But it's just a question of whether it will happen in time.

Ian:

Yeah. That's a lot of pressure on you as an artist if you have to constantly ask, "Is my work worth this flight I'm taking, or this almond I'm eating to fuel my day? Is it worth the destruction to make this thing that I want to make?"

Alastair:

Yes. When I started the project it wasn't even in my mind. The idea of flying somewhere to shoot something wasn't really an issue. And now I still do it, but I'm thinking about it and thinking, "Hmm, this is my job and my career now, and how I'm going to get around this conundrum?"

Part of my inspiration to do this was that I saw some photos by some industrial photographers who were working in the '50s and '60s. Particularly Wolfgang Sievers and Maurice Broomfield. They were working for big industrial manufacturers, photographing their facilities to show the world how amazing they were. So, an oil company would have its oil refinery photographed and then they would say to the world, "Hey, look how amazing we are. Look how big our oil refinery is."

And then that went out of fashion quite quickly. I think by the 70’s and '80s these things were serious eyesores. No one wanted to live next door to one, and the oil companies had gone in totally the opposite direction, and instead of showing that oil refinery they would show a picture of two kids skipping through a field with the sun shining behind them. And now I think it's coming back another way. It's become impossible to pretend that you're not doing anything naughty or that you are totally clean. That's a total no-go now. So, I’ve found that people are opening their doors more than they were when I started eight years ago.

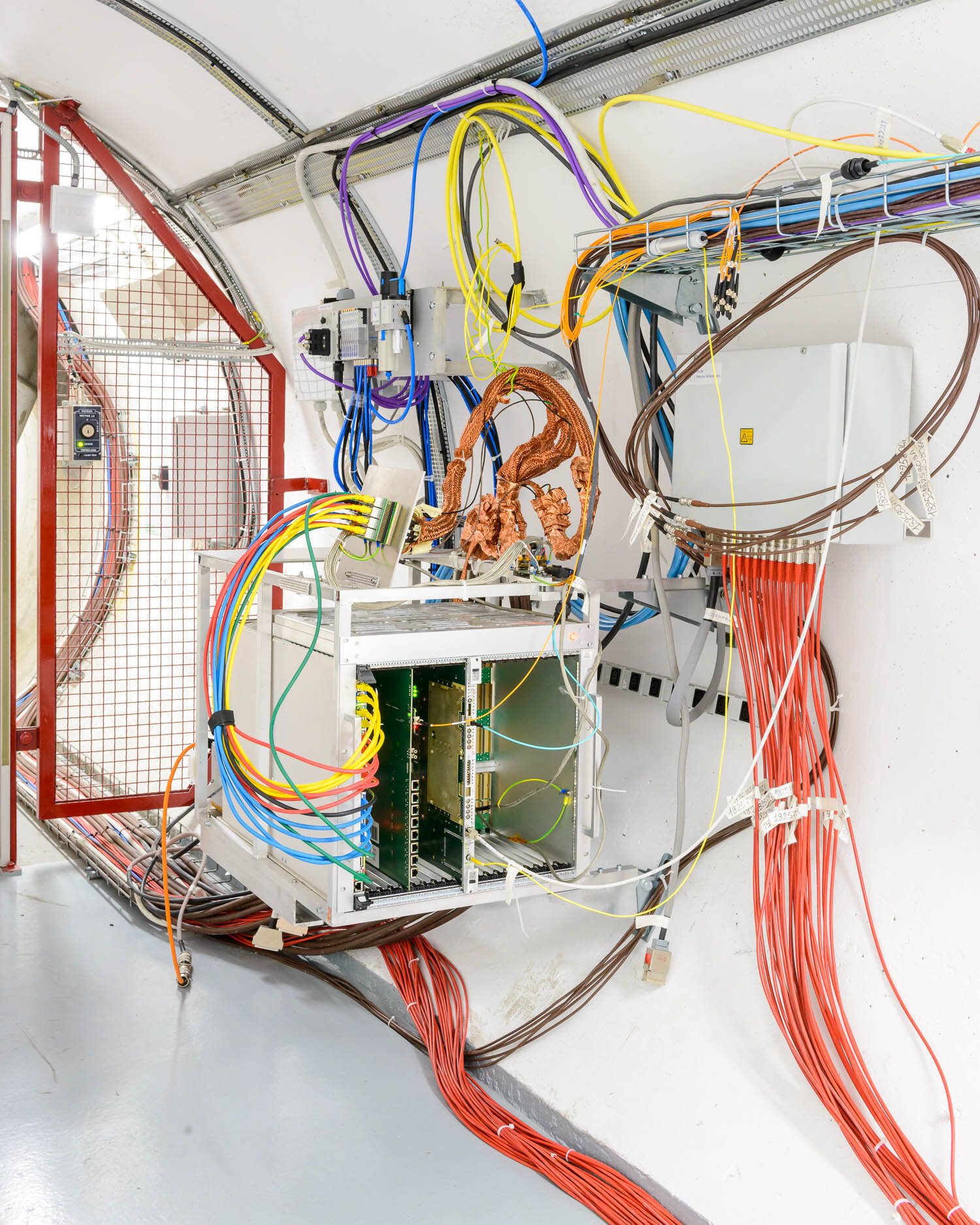

Radio Anechoic Chamber, Technical University of Denmark

Ian:

I want to talk about that, because looking at these images I so often had the thought, "How did he get in here?" Tell me about the process of getting in to take these photos.

Alastair:

When I started it was like a light bulb moment - when I saw the images of those old industrial photographers. I was looking for a new direction and I just thought, "That's what I want to do. That is fascinating.” So, I started calling all sorts of places ... I would call Toyota or someone like that and say, "Hey, I'm a photographer. Can I come into your factory and take some photos?"

I was just calling the number they had on the website, and I got nowhere fast. But then I had a couple of lucky breaks. One of the first ones was at CERN in Switzerland, where they have the Large Hadron Collider. You can go on a public tour, where you don't really see much. They just take you into an auditorium and show you a movie and that kind of thing.

I booked myself on the tour and I wrote to the press office. "Hey, I'm a photographer. Can I see anything else when I'm there? Can you show me anything the public doesn't get to see?" And they wrote back and said, "We've booked in to you to meet this engineer at this workshop, and he will show you around." And then I met an engineer there. He said, "Next time you want to come, just give me a call and I'll show you around anything you want to see. Don't worry about the press office." So, I've been back four times now. Actually they bought all the pictures I took, then hired me to take some more pictures. So, that worked out. In general scientific facilities are easier to access because they want more people to know about what they are doing, they are not trying to hide anything.

I built up a portfolio and had some good press, which I was able to show to the people who I was contacting. And I would either get immediate interest, "Yeah, no problem. That sounds really interesting." Or I would just get no response. And I learned pretty quickly that when I don't get any response it's not going anywhere.

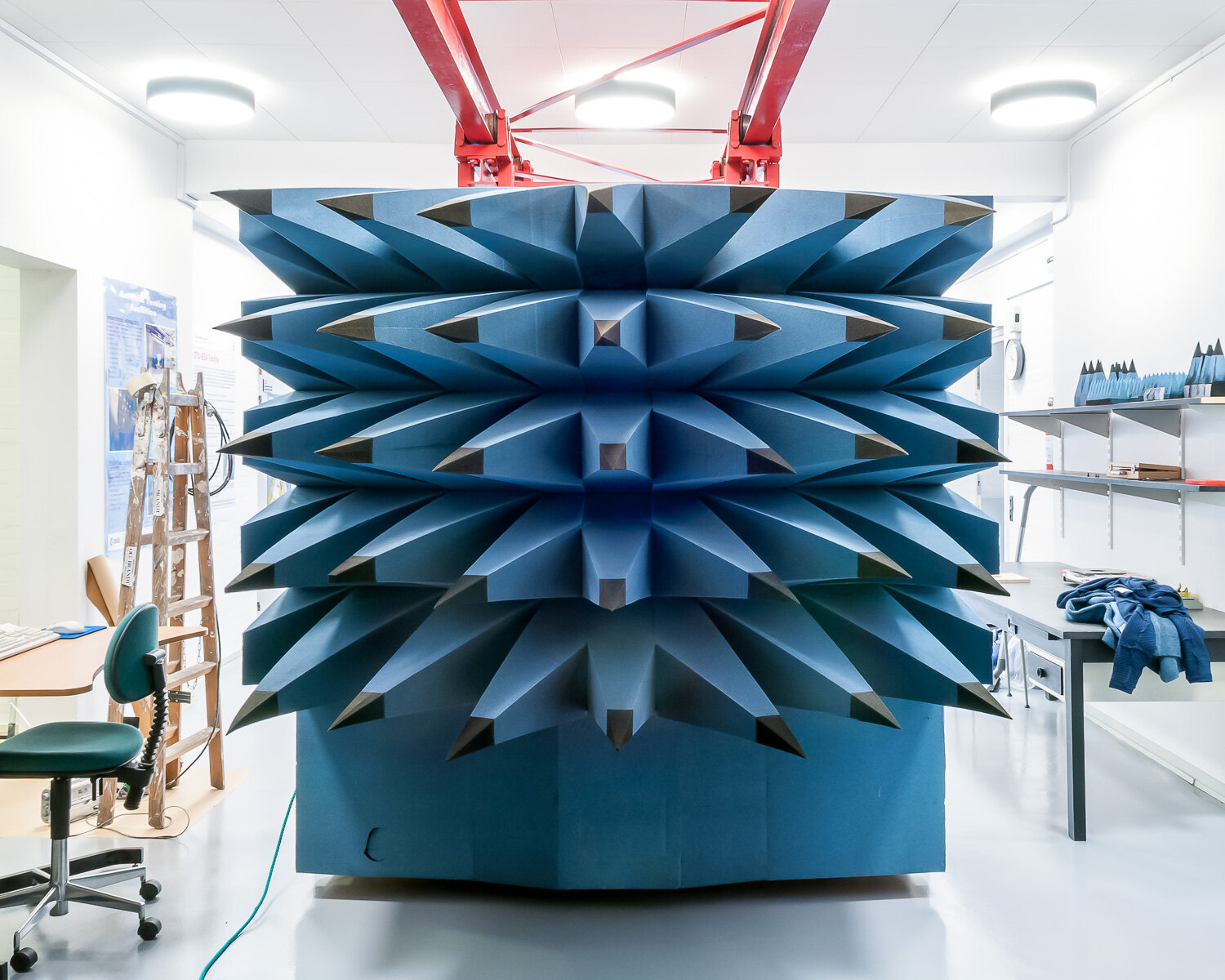

Maersk Triple E container ship under construction, Daewoo Shipbuilding & Marine Engineering (DSME), South Korea

Ian:

I think that you're finding beauty in a lot of places where I would have never imagined there was beauty.

Alastair:

That's the plan. But it's all about how you look at it. I think something I want to do is challenge what people think of as beautiful, because there are a lot of things that you can say are ugly and beautiful at the same time. The title of this book “Unintended Beauty,” is meant to be a bit provocative. A lot of beautiful things should have a bit of ugliness to them. Like the distillery you mentioned, the Absolut Vodka Distillery, when I was growing up I think my parents would have driven past it and just pointed out how ugly this thing is, and thank God they don't live next door to it. And I'm not sure that I would want to live next door to it even now, but I think it's beautiful.

Ian:

Were you always that way, seeing these things where other people weren't?

Alastair:

No, I don't think so. I think I've always been intrigued by things that are a little bit strange, a little bit dark, and perhaps don't quite fit into the conventional idea of what is beautiful or pretty. But I don't think that I started to look at these kind of industrial spaces as being beautiful until I really started to photograph them in this way. Graphically they are very interesting. So, I'd walk into a place and just see lines, and colours, and shapes, which were just immediately visually appealing.

And then comes the element that these things actually do something and mean something. And I have access to this place that other people don't have access to, and I get to see this. And I get to find the angle that I think is interesting, and then that's the angle that comes out and that people see. Then they can make their own mind up about how that makes them feel.

Aurora Nordic medicinal cannabis greenhouse, Denmark

Ian:

This may be a broad question, but the book is called Unintended Beauty, and there is so much unintended beauty in these factories. On the whole, do you think that unintended beauty is more interesting or more beautiful than intended beauty?

Alastair:

No, I don't. I like to be surrounded by beautiful things in my life, and most of them are intentionally beautiful. I think there are comparatively few things that I'm surrounded by in my life that were not intended to be beautiful. Most of the things that I use in my everyday life and that I look at all the time have been designed to look good when I'm holding it or when I'm using it. So, I have a strong appreciation for things that are meant to be beautiful, but I find it more interesting when they're not necessarily supposed to be beautiful.

I enjoy it when engineers or scientists have taken decisions for purely practical purposes, just because this is the most efficient way to make a machine work, and then decided to paint some part of it yellow just on a whim. That a wire should be a certain colour, for no other reason other than the engineer that designed it just thought, "blue."

Ian:

There's the image of the Adidas factory, where the colour is so vibrant, so insane, so, for me, unexpected. And I looked at that and I thought, "Oh, it's so interesting," because I wouldn't have expected this colour. The colours clearly have a purpose. They're organizing this process in some way. And it's so interesting to have colour with a purpose and the beauty that comes from that, but then I think the natural world is that way too. Like, all colours have a purpose. A flower is the colour it is because it needs to attract pollinators.

And a colourful creature is the way it is because that is the way it has evolved to attract mates and continue its species. There's an interesting parallel between this same colour which makes the factory world and the natural world beautiful, but it is just pragmatic in both of those places too.

Alastair:

Something that I think about quite a lot is that when you make a comparison between nature and these factories and laboratories, in one sense we expect these facilities to be the antithesis of nature. It's like humans taking nature and just messing with it.

I think for a lot of people these facilities are symbolic of a lot of things that are wrong with the world. But I often think about the way that we build these places, the way that one person or a group of people have an idea for something, and then like ants we collectively come together to organize insanely complicated infrastructures.

One of the most impressive things that I've seen when I've working on this is not just the physical building or machines. It's the organization that it takes to run these places, and to build the machines - to build a machine like the Large Hadron Collider and organize people from different cultures from all over the world to build such complicated things with such precision. And it works. I know that humans are the only animals that communicate and collaborate on the scale that they do, and that we think differently to other animals, but when you really zoom out and look at the big picture, the only other place I can think of that kind of thing happening is in nature. It's like an ants nest. It's like a beehive. It's the same kind of thing, so it kind of comes back to being very natural in a way.

Ian:

Yeah. Yeah.

Alastair:

So, again, there is this contrast between what is natural and what is unnatural. What is beautiful and what is not beautiful? And what is destroying nature and what is just nature itself?

Sex doll workshop, RealDoll, USA

Ian:

The image of the head of the sex robot, which is essentially the inner workings of the machine with the skin removed, it's so grotesque and there's something so funny about seeing that object with its intended purpose being grotesque. But then I think, if you remove the skin of a human being it would be just as grotesque and maybe more grotesque.

In many of these images, there are no people. And you can kind of imagine the places running entirely without people. You can look at these images and imagine that the facilities are just going constantly and don't need us. But they don't feel empty, somehow. Did you experience that feeling?

Alastair:

I haven't made a conscious decision to not have people in the pictures, but I feel that most of the pictures just work better without people, because I don't want the people to be the focus of the picture. I wanted the place or the machine to be the focus. And these places are not un-human because I see them as direct result of the human brain, so for me there's not a lack of humanity there. This is a representation of humanity. Everything that we want and need is coming from these places, and people have devised these places in order to provide for those needs, and it's all the product of the human mind.

I almost took a decision to only choose pictures which had no people in them for the book. But then there were pictures where the person added something without taking away what I wanted to say, without becoming the focus of the picture. A lot of the times when there are people in the pictures then it's the people that you end up looking at, and I didn't want that to happen.

Large Space Simulator (LSS), European Space Research and Technology Centre (ESTEC), Netherlands

Ian:

I look at this work and I think you're an incredible noticer of things. I think noticing is a skill and a talent that some people have more of than others, and I think you're walking through these spaces and seeing something, which you're pointing out really effectively so that others can see it. It's like you're spreading your ability to notice.

Alastair:

I think it's also something that takes practice. When I first started doing this kind of thing I think I just photographed everything, everything that was in a space. Every angle I could get. I would take hundreds and hundreds of photos. Now I'm much more selective. I have a lot of pictures of wires and pipes going in different directions and I still take them because I love them. I can't get enough of really messy wires and pipes. I could just photograph them all day. But I am more selective and I know what I'm looking for when I go to a place.

And I get quite frustrated sometimes when I can see the thing in real life that I want to capture in a picture, but I can't always make it happen. I go to places where, with my eyes, and my sense of smell, and my ears I can have this experience that I want to try to capture in a photo. And sometimes I can get that and I'm really, really happy, and sometimes it just doesn't work out. So, yeah, I guess it’s like that with everything in life.

Spark gap in the High Voltage Laboratory, Technical University of Denmark

Ian:

Did you ever read the book The Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, the Mark Twain book?

Alastair:

No, I haven't.

Ian:

The premise is that this American from, I guess, the 1800s gets transported back in time somehow to Camelot, and he uses his advanced knowledge of science and the way things work to survive and to prosper. That’s a very short version, but basically he had skills from the future that allowed him to prosper in the past.

Alastair:

A bit like Back to the Future 2?

Ian:

Yeah. But more like he could use his knowledge of science to seem like he was a wizard. And sometimes I think about if I were transported back a thousand years, I actually know very few things they don’t. There’s very little I would be able to do. It's very easy to live in the world and not understand how any of these things came to be.

Alastair:

I totally hear what you're saying. I'm also very good at kind of getting an understanding of things when they're being explained to me, and then very quickly forgetting about it when I try to explain it to somebody else later on.

Ian:

Yeah. There should be a name for that phenomenon. It happens all the time to me.

Alastair:

There's a quote which at the front of the book by Carl Sagan and he says, "We live in a society exquisitely dependent on science and technology in which hardly anyone knows anything about science and technology."

Danish Crown’s Horsens Slaughterhouse, Denmark

Ian:

There's an image of a sex toy factory and an assembly line of sex toys. And those objects in particular are so personal, and they're used so personally, and there's something strange about looking at them in multiple in this industrial setting. This is a thing that when you have one you maybe don't want to consider that there are thousands of identical things in thousands of bedrooms around the world. It's very striking to be confronted with that.

Alastair:

I was truly shocked when I went to the dildo factory about quite how many really, really large dildos they're producing, and obviously selling. My idea about what people out there in the world are sticking inside themselves has changed since I've been to that factory. It's become a lot more extreme! I actually travelled to California because I wanted the sex element to be in this project. I'm interested in these things that end up being used on a very personal level.

I think, again, there is a comparison with the slaughterhouse. Meat and sex toys are products that many people have a relationship with to some extent whether they like it or not, both can be controversial, and it was important for me to include those kind of taboo products in the project. I also can’t help smiling when I see the dildos, and I like the visual association with the sausages and the pigs.

But I think that I'm also attracted to the contrast between things that end up being very, very personal, like a dildo, and things which are so abstract, like at CERN trying to find out how the universe started. There are two very big extremes there. On the one hand, most people in the world have some kind of relationship with a dildo - well, if they don’t have a relationship with it they at least understand what it does – but there are very, very few people that understand the experiments that are going on to try and figure out how the universe started.

But machines are providing the solutions to both of those problems. Machines are giving the answers to where the universe comes from, and they're also giving you your dildo. And these machines are all products of our minds. So, it keeps coming back to the way that these machines provide for our needs, and embody our hopes and our dreams.