For $200,000 you can have your body cryogenically preserved after death. The question is: To what end?

Published in Bloomberg Businessweek December 2023

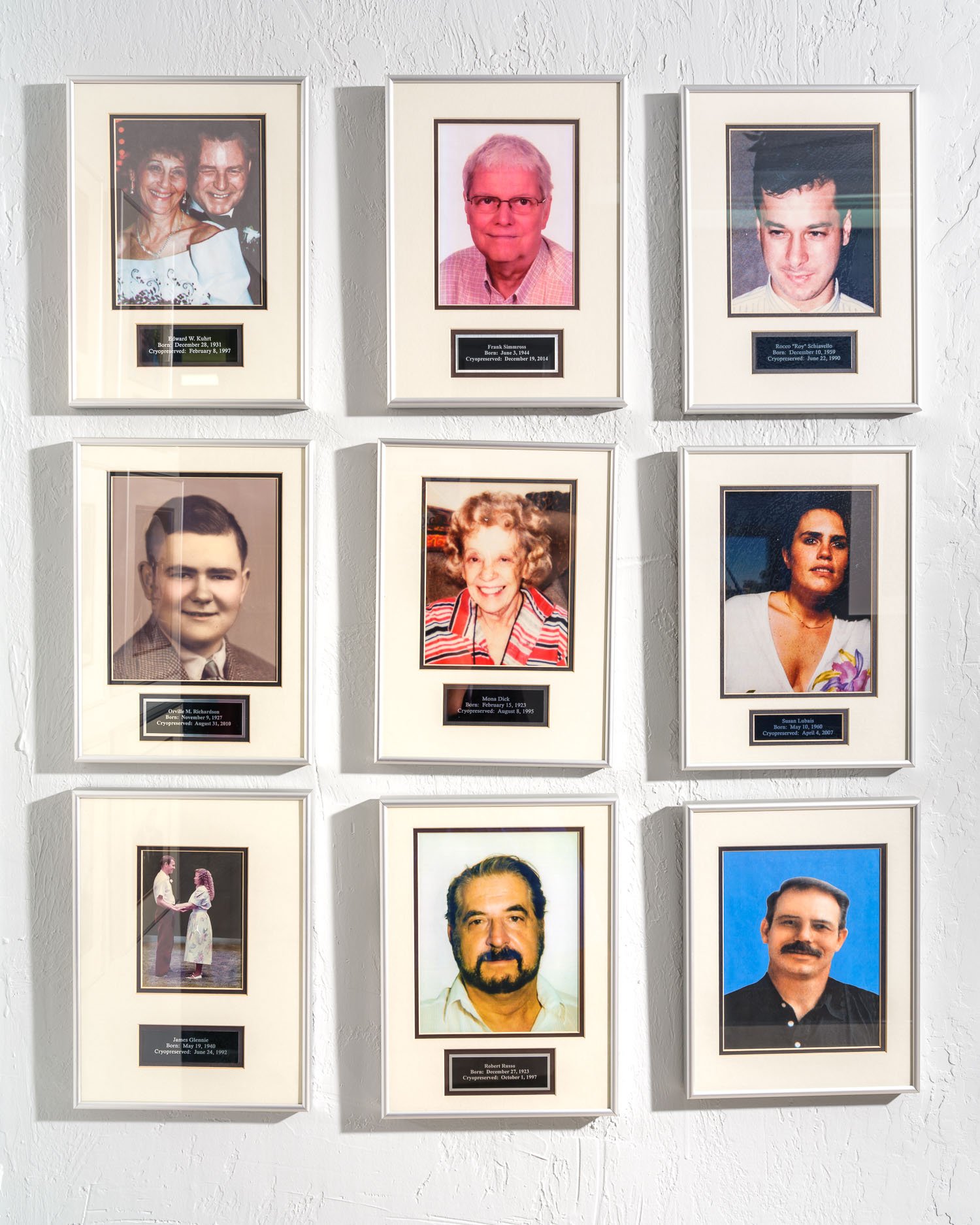

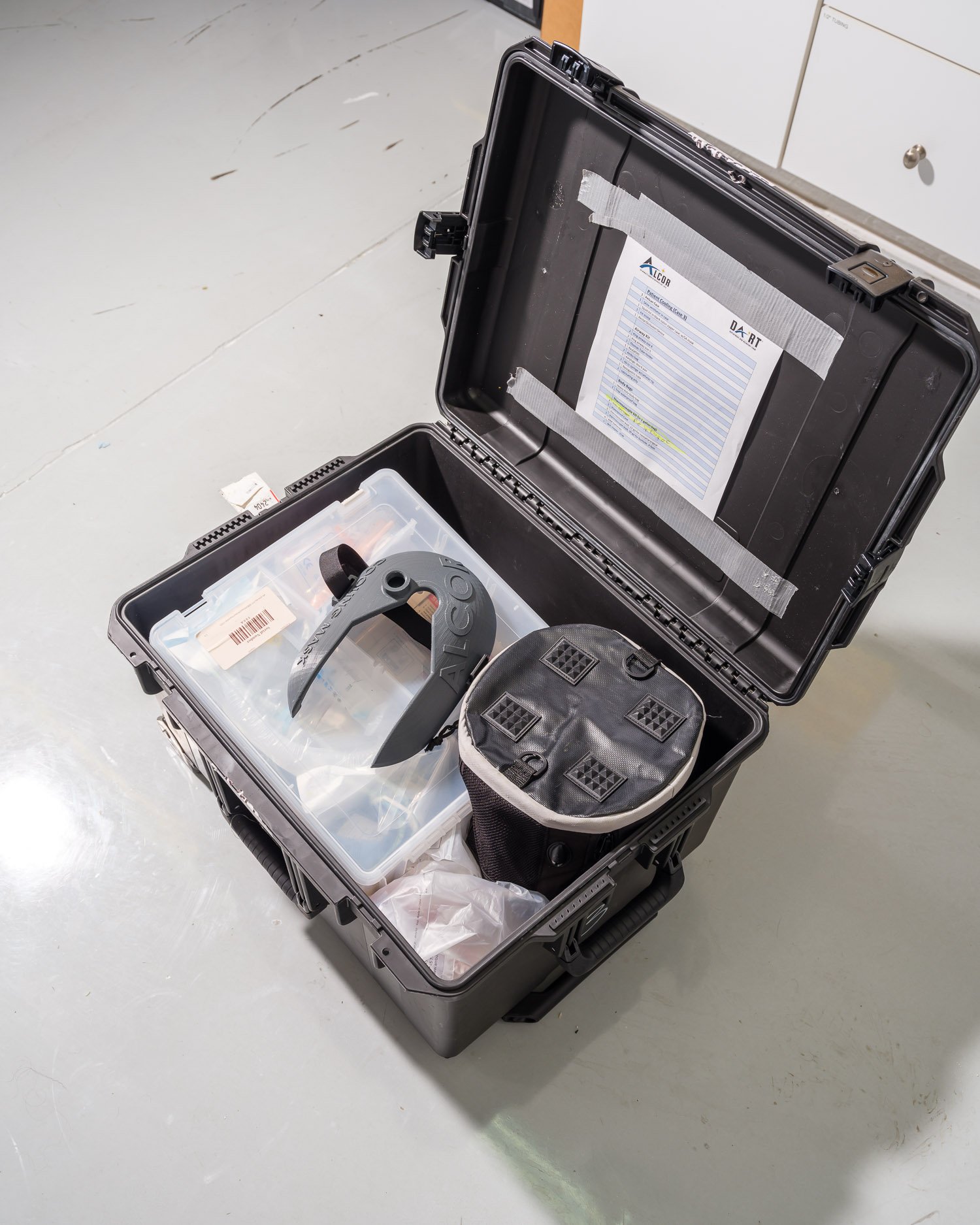

Above: The Operating Room at Alcor. Upon arrival at Alcor, cryoprotectants such as M22 are perfused into the bloodstream to reduce and prevent freezing. Uncontrolled freezing would cause damage to the blood vessels, brain, and other organs. Perfusion prepares the patient for cryopreservation; A dummy showing the post-death cooling procedure at Alcor. The cooled patient is carefully transported to Alcor’s operating room in Arizona. Many Alcor members choose to retire and/or enter hospice near Alcor for shorter transport time and better procedural outcome.

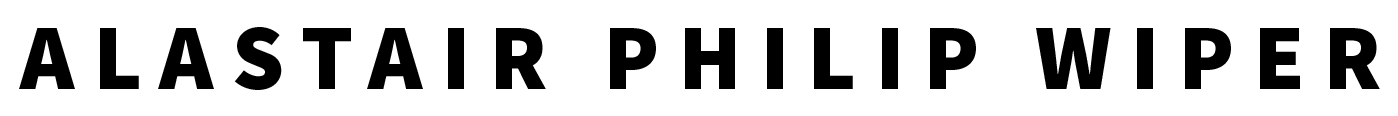

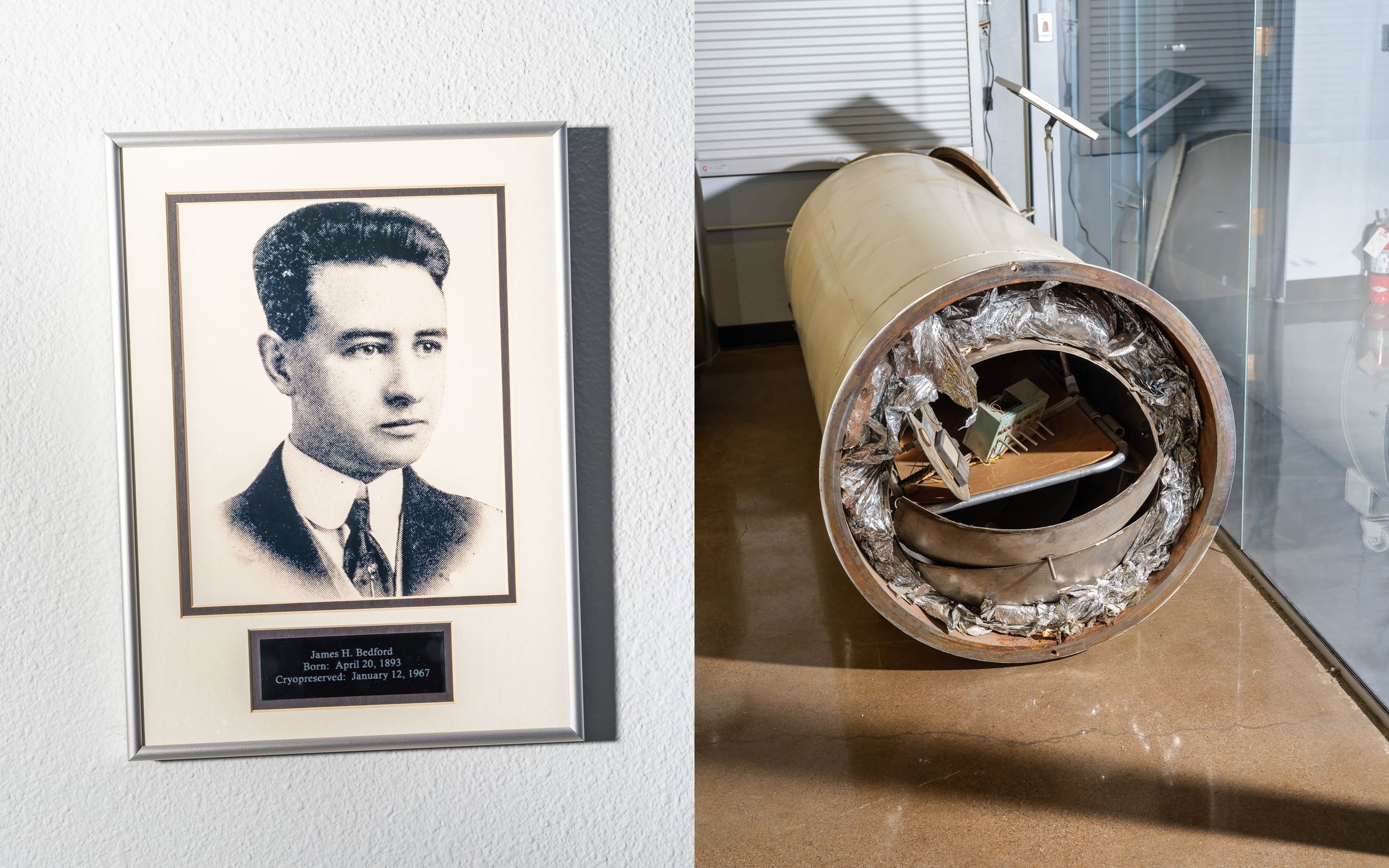

A tour of Alcor Life Extension Foundation’s headquarters in Scottsdale, Arizona, includes some unique sights. The non-profit has more than 200 human bodies or heads—and a few beloved pets—in cryogenic preservation on-site.

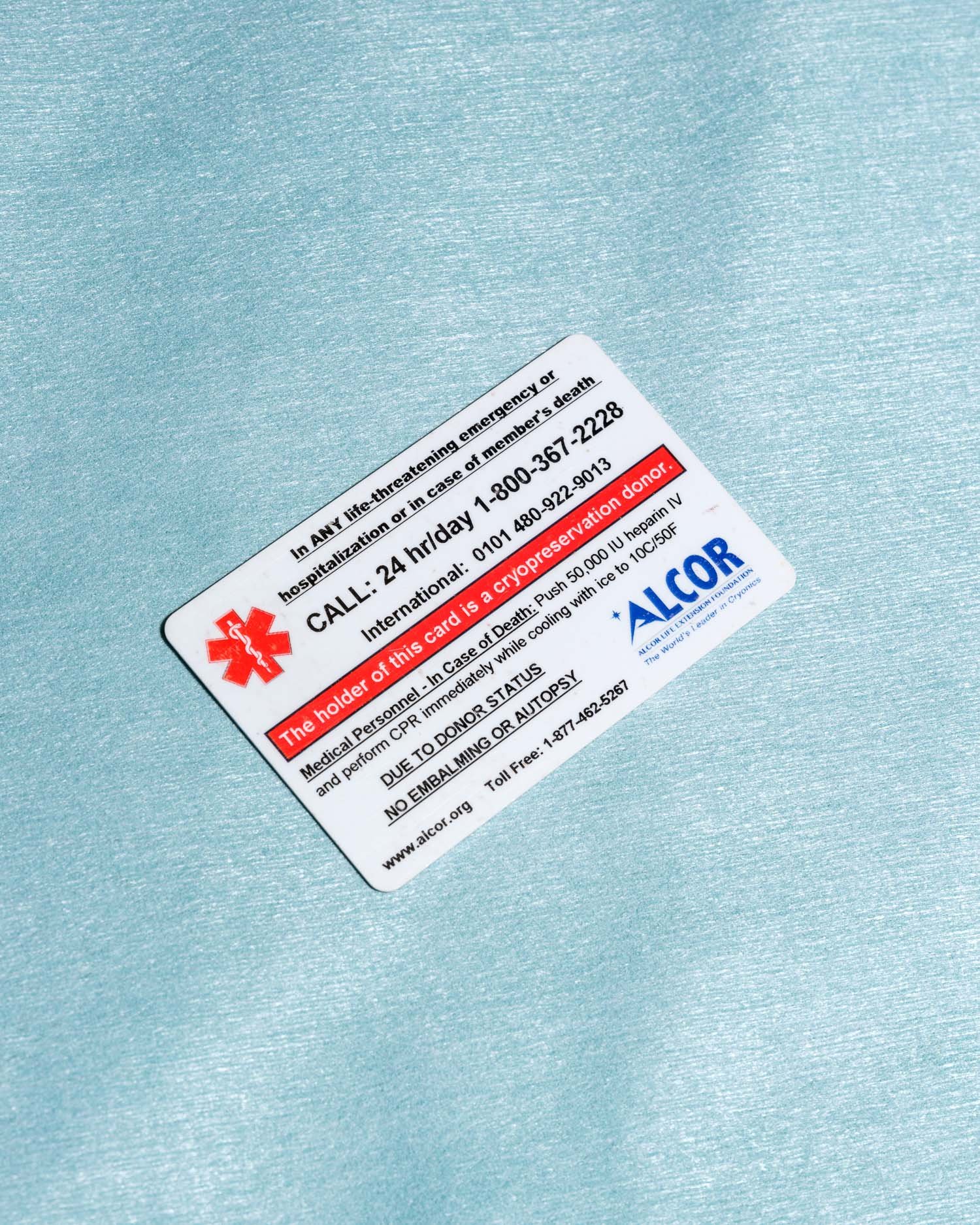

Founded in 1972 by Fred and Linda Chamberlain, Alcor is dedicated to cryonics research and education and has about 1,500 members planning on some form of cryogenic preservation. While they’re still living, members wear medical alert bracelets that instruct hospitals and doctors to contact the organization in the event of a life-threatening emergency. A team is on standby to rush the body of any member who dies to Alcor’s facility. There, bodily fluids are replaced with special solutions that won’t turn to ice during the next step in the preservation process—cooling the cadaver to -196C (-321F).

Care Services Manager Dr. R. Michael Perry, who has worked at Alcor since 1989. Dr. Perry monitors Alcor’s dewars, provides facility surveillance during off-work hours, and performs writing tasks and computer programming.

The operation required to process and protect a body upon arrival is extensive, and the chemicals used for vitrification are unique, accounting for the hefty price tag: $200,000 for the whole body or $80,000 for just the head, plus monthly membership fees of up to $100. (Most members pay by designating Alcor as the beneficiary of their life insurance policies.) User fees cover about 40% of the cost, with the rest coming from donations.

James Arrowood, co-chief executive officer of Alcor, describes cryogenics as a serious scientific undertaking, deemphasizing the more outré associations it has in the public imagination as just a way to cheat death. He sees scientific research as the heart of Alcor’s mission. “I know what happens if I choose cremation,” Arrowood says. “I know what happens if I choose burial. I also know what the loss is to the science.” He gives the example of Albert Einstein’s brain, which was removed for study but was cut into pieces because there was no way to preserve and examine it in a non-destructive way. If there had been, Arrowood says, we could have learned more about the unique nature of the scientist’s genius. “Einstein’s brain is all over the world in little chunks,” he says. “And you can never get that data back.”

The bodies are placed upside down, in sleeping bags inside the dewars. They are upside down so that if there is a problem that means liquid nitrogen cannot be topped up (such as an apocolypse) the heads will be preserved longest. Many choose to have only their heads preserved (known as neuropreservation) since this is considered the most important organ of the body to protect, without which no other part of the body would function.

Alcor has accumulated a repository of data on organ preservation and decay that spans more than five decades. It has in storage the brain of someone born in the 1880s and someone born in the 2000s. Much of what it was doing in its early years was aspirational and felt like science fiction, Arrowood acknowledges, but he adds that cryogenics isn’t as weird as it’s made out to be. With in vitro fertilization, “embryos are frozen indefinitely,” he says, “and they ultimately result in a living being.”

As technology has progressed, advances such as improved preservation of individual organs have become viable goals. Arrowood cites kidney donation as an area in which Alcor might be able to make a difference—notably by preserving kidneys long enough after a donor’s death to line up a match and arrange for surgery. “That is a solvable problem,” he says. “It’s not fiction.”

Co-CEO/President, and General Council of Alcor, James Arrowood started working with Alcor in 2015 as outside General Counsel. He became Co-CEO in 2022.

Arrowood also sees potential for Alcor to contribute to scientific knowledge about what happens to bodies after death and to serve as a kind of seed bank, helping preserve species that are near extinction.

Naturally, he’s planning to be cryopreserved himself. “Have you seen a cremation? They’re awful! Or burial? You get eaten by worms! I’ve never liked worms,” he says. “I am choosing to be a part of a supercool science experiment.”