Knitted textile being cut at Innofa textile mill, Kvadrat Febrik, Netherlands, 2019

Legend has it that in the seventeenth century Tilburg’s citizens were famous for saving their urine in jars and then using it to wash wool (it contains ammonia, an important chemical in processing wool). They filled baths with a mixture of water and urine, heated the mixture to 50o Celsius, and washed the wool in it. Apparently at one point a bucket of urine cost half a Dutch penny. It’s good to know that Kvadrat Febrik does not use urine nowadays when making fabrics at their Tilburg factory. The company uses circular knitting machines, which have around 4,000 small needles to knit wool in a continuous loop with no seams; the fabric is then cut to create one wide, flat piece of textile. The machines allow the firm to be very flexible and produce very small quantities and samples of new designs.

Doc Johnson Dildo Factory, USA, 2019

Doc Johnson is the largest US manufacturer of adult pleasure products, with 450 employees producing 75,000 products per week in their Los Angeles factory. "The only type of products that we make here are dildos, dongs, butt plugs, anal products, and strokers or masturbators,” says COO Chad Braverman. It would take less than a year for the factory to produce one of these for every single person living in Puerto Rico. Electronic products such as vibrators are produced abroad and added to the 75,000 per week.

Maersk Triple E container ship under construction, Daewoo Shipbuilding & Marine Engineering (DSME), South Korea, 2014

When it was built the Maersk Triple E was the largest container ship in the world, with a capacity of 18,000 containers: enough space to transport 864 million bananas. Twelve of these ships were in different stages of construction when I visited the DSME shipyard, where 46,000 people are building about 100 vessels and oil rigs at any time. It could reasonably be described as the world’s biggest Legoland: the ships are built in sections called megablocks, which are then lifted into place with cranes and welded together.

Large Space Simulator (LSS), European Space Research and Technology Centre (ESTEC), Netherlands, 2013

Established in 1968 in Noordwijk, ESTEC is the European Space Agency’s (ESA) main development and test center for spacecraft and space technology. At some point almost all the equipment launched by the ESA will be tested here. About 2,500 engineers and scientists work at ESTEC, which is where European space missions are born. Space is not a very nice place to be, and it takes a hell of a lot of effort and money to put something up there—and, once it is up there, it had better work, because it isn’t going to be easy to fix.

The LSS, the largest vacuum chamber in Europe, is used (as the name suggests) to simulate the conditions of space. And it is large: so large that whole spacecraft can fit inside it. Opened in 1986, the LSS creates a vacuum a billion times less than sea-level atmospheric pressure and chills the chamber down to the cryogenic temperatures of space. A powerful array of xenon lamps, reflected off hundreds of small mirrors, reproduces the unfiltered sunlight encountered in Earth orbit, and the piece of equipment under test is then rotated to examine how these extreme fluctuations in temperature will affect it. Tests on a piece of equipment can last for weeks at a time, as the change in temperature constantly cycles to reproduce the quick shifts in temperature caused as spacecraft move in and out of sunlight.

Sex doll workshop, RealDoll, USA, 2019

Twenty years ago RealDoll’s founder, Matt McMullen, began producing dolls in his San Marcos workshop, and now the company makes around thirty per month. RealDoll was born when Matt wanted to make a more realistic mannequin for shop windows. “My initial efforts were beautiful women . . . I wanted them to be poseable so that the position wouldn’t be rigid . . . so you could manipulate them into different poses. Then people’s imagination got the better of them, and they were going ‘Hey, I want to have sex with that thing.’” Men began approaching Matt, asking if they could buy dolls, and if he could make them anatomically correct so that they could have sex with them. Matt obliged, and hasn’t looked back. Matt then decided to explore artificial intelligence. The company has just shipped its first five robotic heads, and plans to produce five per month from now on. A regular doll, which is fully customizable from nipples, to lips, to type of vagina (there are more than ten) averages approximately $7,500, and a robotic head will add an extra $8,000 to the bill.

RealDoll sex doll, USA, 2019

"The whole mouth comes out for cleaning, but the tongue actually has four sides. You can do a fat tongue down, fat tongue up, skinny tongue up, skinny tongue down. You know, like she's licking her lips or whatever. But they all come with the flexible teeth and tongue." A RealDoll on the production line.

adidas shoe factory, Indonesia, 2017

Adolf Dassler began making shoes in his mother’s kitchen on his return from World War I, and was joined shortly after by his brother Rudolph. In 1936 Adi drove to Berlin to persuade Jessie Owens to run in Dassler running shoes (the first sponsorship of an African-American), and Owens’ four gold medals assured interest in Dassler’s shoes from the sports world. During World War II the brothers split after a huge argument, which led to the establishment of adidas (Adi- Das- sler) and Ruda (Rudi-Dassler). Ruda later became Puma, and a rivalry was born that exists to this day. Both adidas and Puma are still headquartered in Herzogenaurach, and throughout the years the town has been split down the middle over which brand to support—even the two football teams are each sponsored by one of the brands. The brothers died with- out making peace with each other, and, although buried in the same small cemetery, are said to be placed as far apart as possible.

At adidas’s Parkland World Indonesia factory 10,000 workers churn out 75,000 pairs of shoes a day (22 million a year). This building is producing adidas Superstars. Shot as part of a project in collaboration with human science strategic consultants ReD Associates.

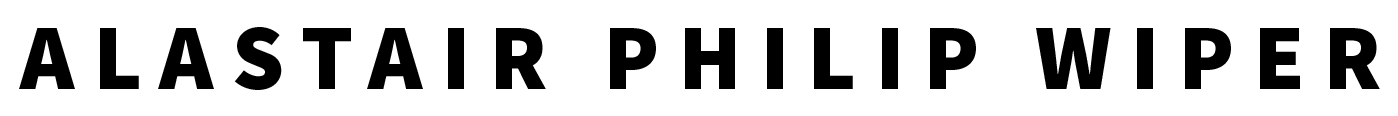

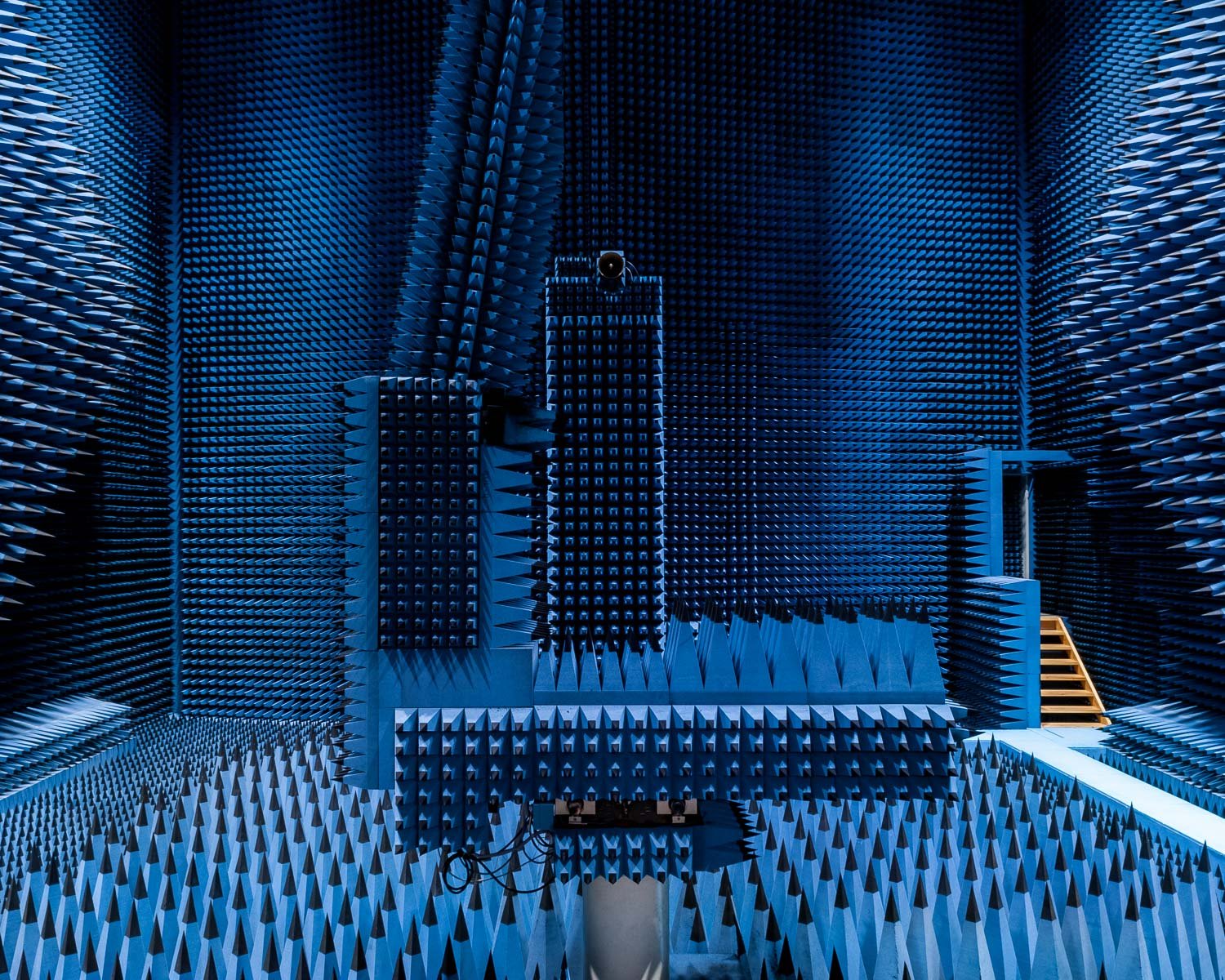

Radio Anechoic Chamber, Technical University of Denmark, 2012

This facility opened in 1967, and currently operates with the European Space Agency (ESA) to test microwave antennas for use in satellites and mobile networks, among other things. The idea is to minimize any reflections of microwaves, and the big foam spikes are filled with carbon and iron to absorb radio waves. This tests the effectiveness of the anten- nas without any external intrusion, simulating the conditions of, for example, space. Many of these chambers are blue; according to Sergey Pivnenko, the professor in charge of the chamber, most of them were black in the old days—until some bright spark noticed that it was a bit depressing to work in a black spiky room all day, so the manufacturers of the spikes started making them in blue.

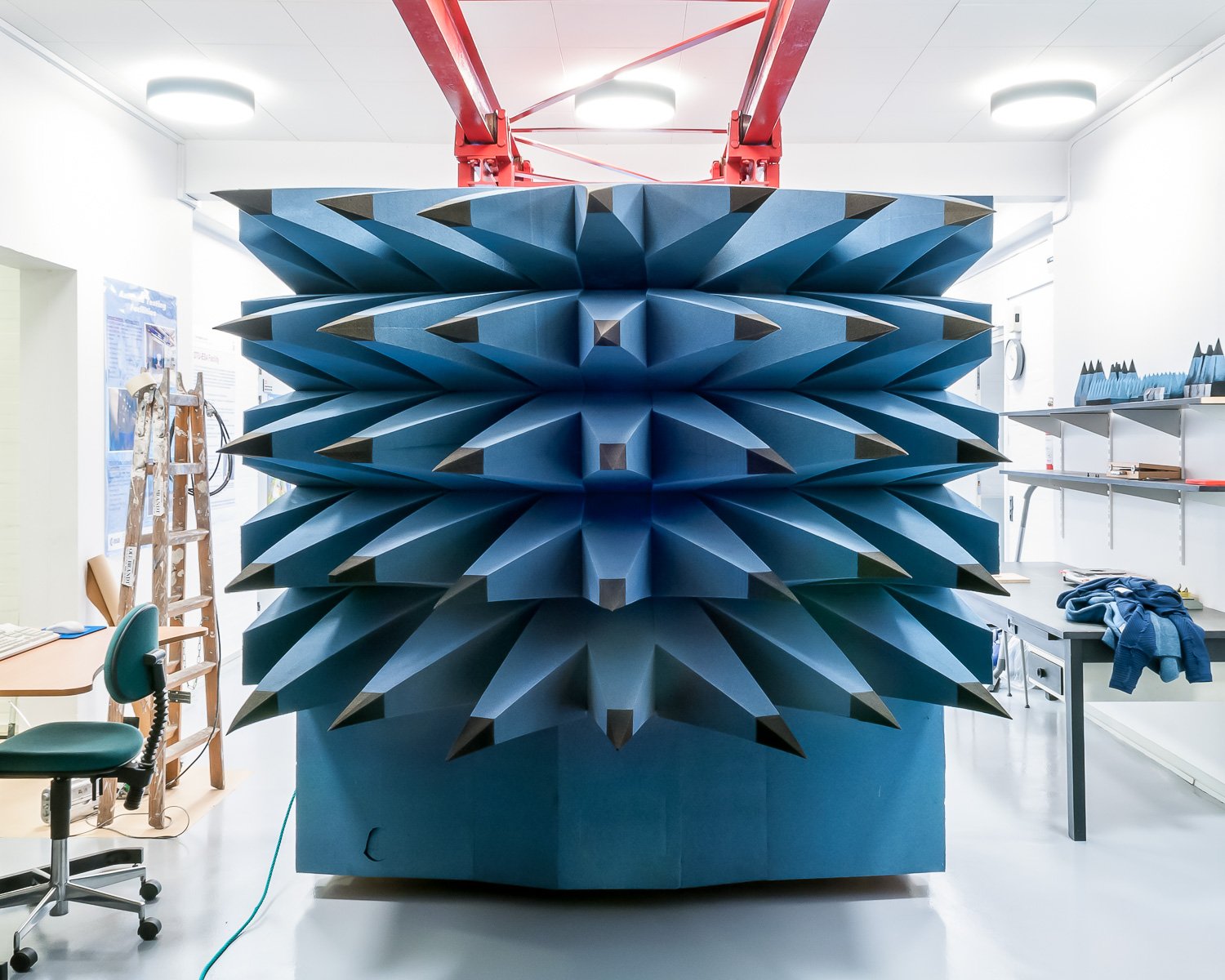

Door to the Radio Anechoic Chamber, Technical University of Denmark, 2012

Creel full of yarn making a warp at Wooltex textile mill, Kvadrat, United Kingdom, 2016

The area surrounding Huddersfield has long been renowned for the quality of it's textile mills, but as is the way with such industries in the developed world, the last 50 years has seen a steady decline as business is lost to cheaper manufacturers in other countries. As mills closed and were turned into offices and apartments, the market for high-end production of textiles opened up and the knowledge and skill of the manufacturers in the Huddersfield area began to be appreciated once again.

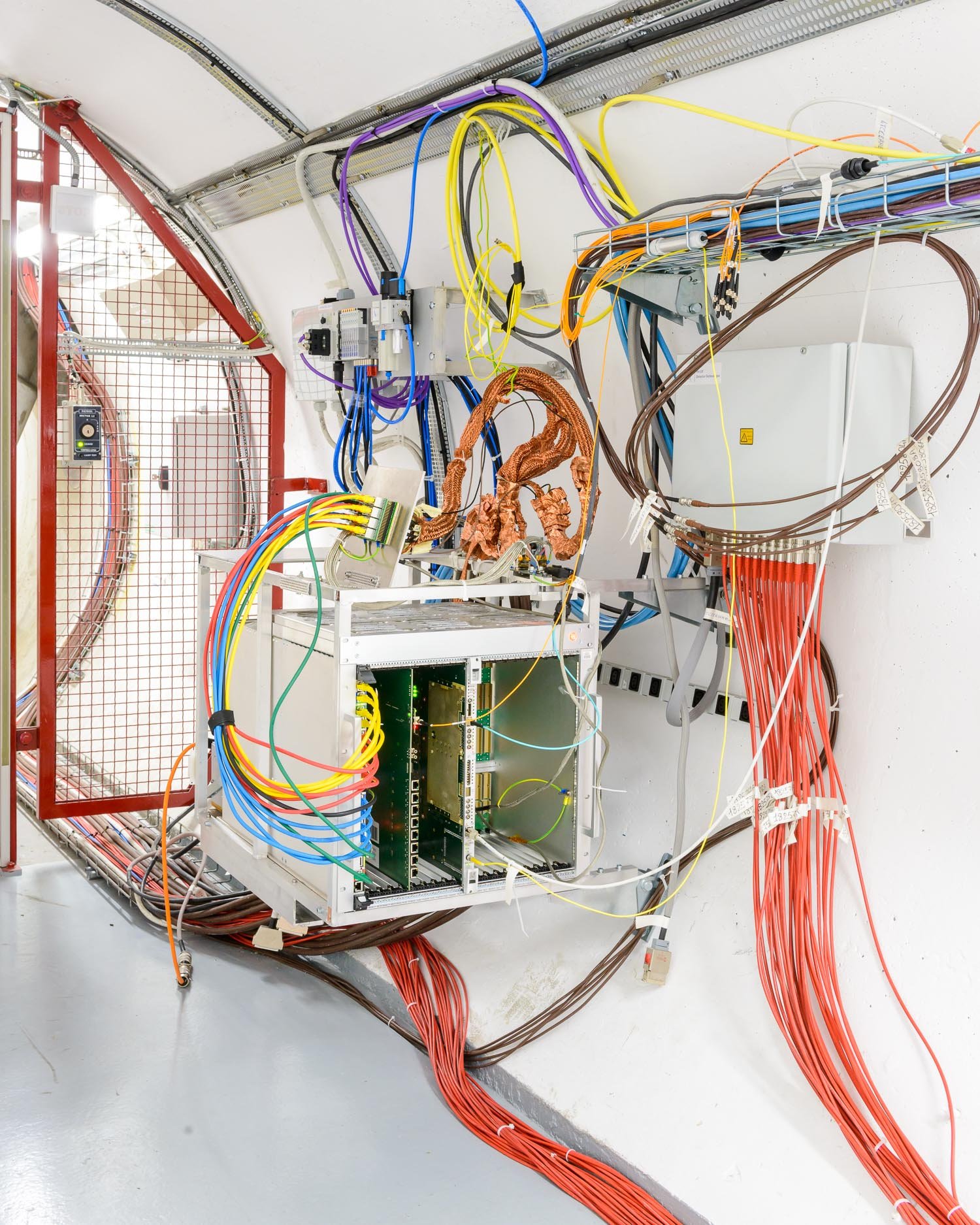

Access Tunnel in the Large Hadron Collider beauty (LHCb) experiment cavern, CERN, Switzerland, 2017

The LHCb experiment is one of the seven detectors collecting data from the collisions of the LHC. The experiment

is all about trying to understand the Matter–Antimatter asymmetry of the universe by studying “bottom-quarks”. When the bottom-quark was discovered in 1977 (during collisions that produced “bottomonium”), some physicists decided that “bottom” wasn’t a very elegant name and so called it “beauty” instead, presumably to stop people like me making fun of it.

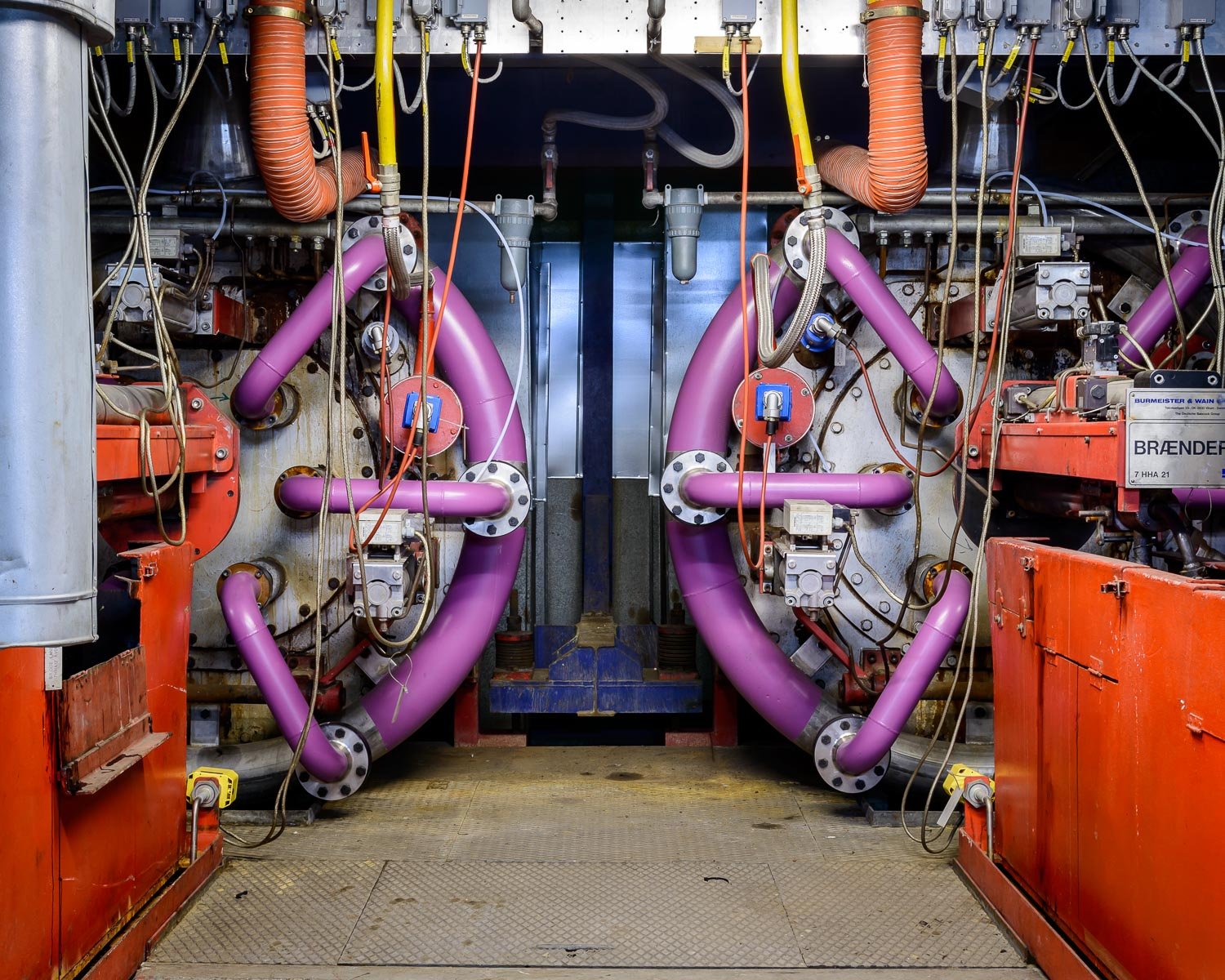

Gas Burners at H.C. Ørsted Power station, Denmark, 2013

When it opened in 1920, H.C. Ørsted’s Power Station was the largest in Denmark, providing enough power to supply the whole Copenhagen area with lighting, and reducing the city’s previous three power stations to backup stations. In 1994 it was converted from using coal and diesel, to natural gas, and to providing district heating rather than power. The power station is operated by Ørsted.

Danish Crown’s Horsens Slaughterhouse, Denmark, 2013

Of the pork slaughtered in Denmark, 90 per cent is exported, and Danish Crown is the world’s largest exporter. Completed in 2004, the slaughterhouse at Horsens kills approximately 100,000 pigs a week, making it one of the largest in the world. It employs 1,420 people and receives around 150 visitors per day. The slaughterhouse was designed with openness in mind— every step of the production, from the pigs arriving, to the slaughter itself, to the butchering and packaging, can be seen from a viewing gallery.

Odeillo Solar Furnace, France, 2012

Opened in 1970, the largest solar furnace in the world works on the same principle as its older, smaller brother just down the road at Mont-Louis (pp. 40–41). The sun’s energy is reflected via a series of 9,600 mirrors and concentrated on one very small point to create extremely high temperatures. It is still used by space agencies like NASA and the ESA as well as scientists and technology companies to research the effects of extremely high temperatures on certain mate- rials for nuclear reactors and space vehicle re-entry, and to produce hydrogen and nanoparticles. In this photo, the grey structure in the center of the reflector array is where the sun’s rays are focused onto a point about the size of a cooking pot, where temperatures reach 3,500°C.

“The Octopus”, a machine that sucks plastic pellets around the factory, Playmobil, Malta, 2015

The German Playmobil company produces all its figures on the Mediterranean island of Malta, and has done since 1976—and over 3 billion have so far been made in the factory there. Today, 1,300 people work in Malta’s second-largest factory, with 270 injection- molding machines creating up to 100 million figures a year.

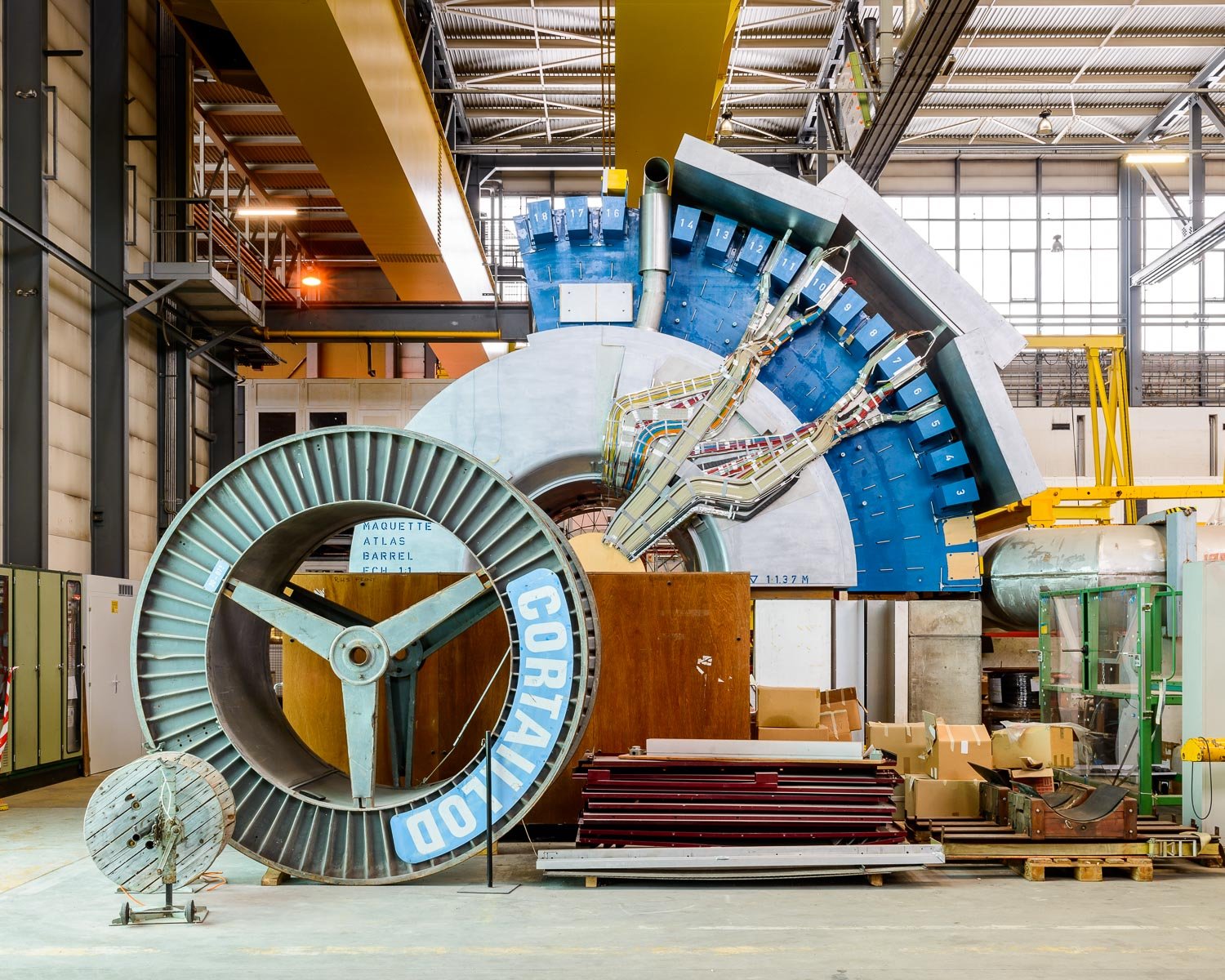

Plywood mock-up of part of the ATLAS Detector, CERN, Switzerland, 2013

A stone’s throw from Geneva airport are the laboratories of CERN, the birth- place of the internet and the home of the world’s largest particle accelerator. Since 1954, thousands of the world’s brightest minds have worked at CERN, using the particle accelerators to help uncover what the universe is made of and how it works.

The best-known particle accelerator at CERN is the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), which sits in a circular tunnel 100m under the ground, stretching from Geneva airport to the Jura Mountains in a 27km loop. The main task of the LHC is to smash protons together with a lot of energy and analyze the results. Protons are fed through a series of particle acceler- ators (circular tubes that use magnets to speed up the protons, thus creating more energy) until they are going extremely quickly. When they are going fast enough, they are shot out into the LHC in opposite directions to travel the full 27km, picking up more speed along the way, and then they smash head on into each other at just the right point. This has been compared to firing two needles across the Atlantic and getting them to hit each other. The most famous discovery by the LHC is of the Higgs boson particle in 2012.

The Atlas Detector is the largest of seven detectors on the Large Hadron Colider, and this model of a small part of the detector was used to test wiring scenarios before installation. I found it at the back of a warehouse gathering dust.

Aurora Nordic medicinal cannabis greenhouse, Denmark, 2019

Mads Pedersen, a third-generation tomato grower, is the owner of Scandinavia’s largest tomato-growing empire, Alfred Pedersen & Sons. Around 2015 Mads realized that his infrastructure and know-how could be applied to growing me- dicinal cannabis. Mads’s new idea coincided with a huge surge in Danish public interest—and political debate— about medical cannabis, and, just as his plans were coming to fruition, the Danish parliament began issuing trial licenses to produce medical cannabis. Mads snapped up the first one and began building a 60,000-square-meter facility, the largest in Europe.

Absolut Vodka Distillery, Sweden, 2017

Established in 1879, Absolut Vodka is the third biggest spirit brand in the world, and all the 99 million liters produced every year are made here in Skåne, southern Sweden. Over one kilogram of wheat is used in each bottle of Absolut, all of it grown locally. The wheat is milled, blended into a mash with water for 3 hours, yeast is added and the mash then ferments for 48 hours, after which the alcohol level is 10%. The mixture is then continuously distilled, and the result- ing fine spirit is 96%. It then moves to a bottling plant and is diluted to 40%. The 11-storey-high storage warehouse in Åhus, contains up to 13 million bottles at a time. Shot as part of a project in collaboration with human science strategic consultants ReD Associates.

Spark gap in the High Voltage Laboratory, Technical University of Denmark, 2016

Built in the early 1960s, this laboratory has since been in constant use teaching the fundamentals of high-voltage tech- nology, and researching and testing electric power components for Danish companies. Shown here with the professor in charge of the lab, Joachim Holbøll, who has worked at DTU since he received his Ph.D there in 1992.

Doc Johnson Dildo Factory, USA, 2019

“It’s a family business,” explains Chad Braverman, whose father Ron started Doc Johnson, the largest US manufacturer of sex toys, 1976. "I wasn't really aware of what my family did for a living for a really long time,” says Chad. "I think there were some years where I thought my dad might be in the mafia or something ... Ron was in “import-export", which as a kid you don't know what “import-export" means. I mean, he kind of has the Tony Soprano look anyways, so I just wasn't sure ... I knew my dad had money. I just didn't know 100% how he got it, because I was just a kid.” Chad remembers visiting the factory once and seeing some “product” that he wasn’t supposed to see. "As I got older, I realised like, I was seeing ... I knew I saw penises. I knew they were penises, because I had a penis. That's how I could do the correlation. It was like, ‘but what would my dad have penises in his place of business for?’ That part I didn't know.”

Freshly Stuffed Salami at the Gøl Sausage Factory, Denmark, 2016

Gol's factory in Svenstrup, Denmark, has been producing sausages since 1934. The pillars of Danish food culture are shaped out of this processed and congealed pork meat, and if you take different shapes and spice blends into account, the factory produces more than 200 types of sausages, salami, pepperoni, and cold cuts for both retail and the catering industry.