Big Ben has just finished a massive renovation, and I was invited inside to photograph behind the clock face. Thanks to Wired - read all about it from the article in Wired November 2022 below!

A Gothic Revival

London’s beloved Big Ben is emerging from an £80 million overhaul that used digital ingenuity to future-proof ‘the smartphone of 1859’.

Words by Alex Doak.

Visitors to London’s Westminster are forgiven for having been confused lately. Ever since scaffolding started peeling from the Houses of Parliament’s Elizabeth Tower—or Big Ben to most—it’s been acting rather erratically. Surely, after its £80 million and six years of conservation work, the world’s most accurate public, or “turret” clock, should be ticking better than ever?

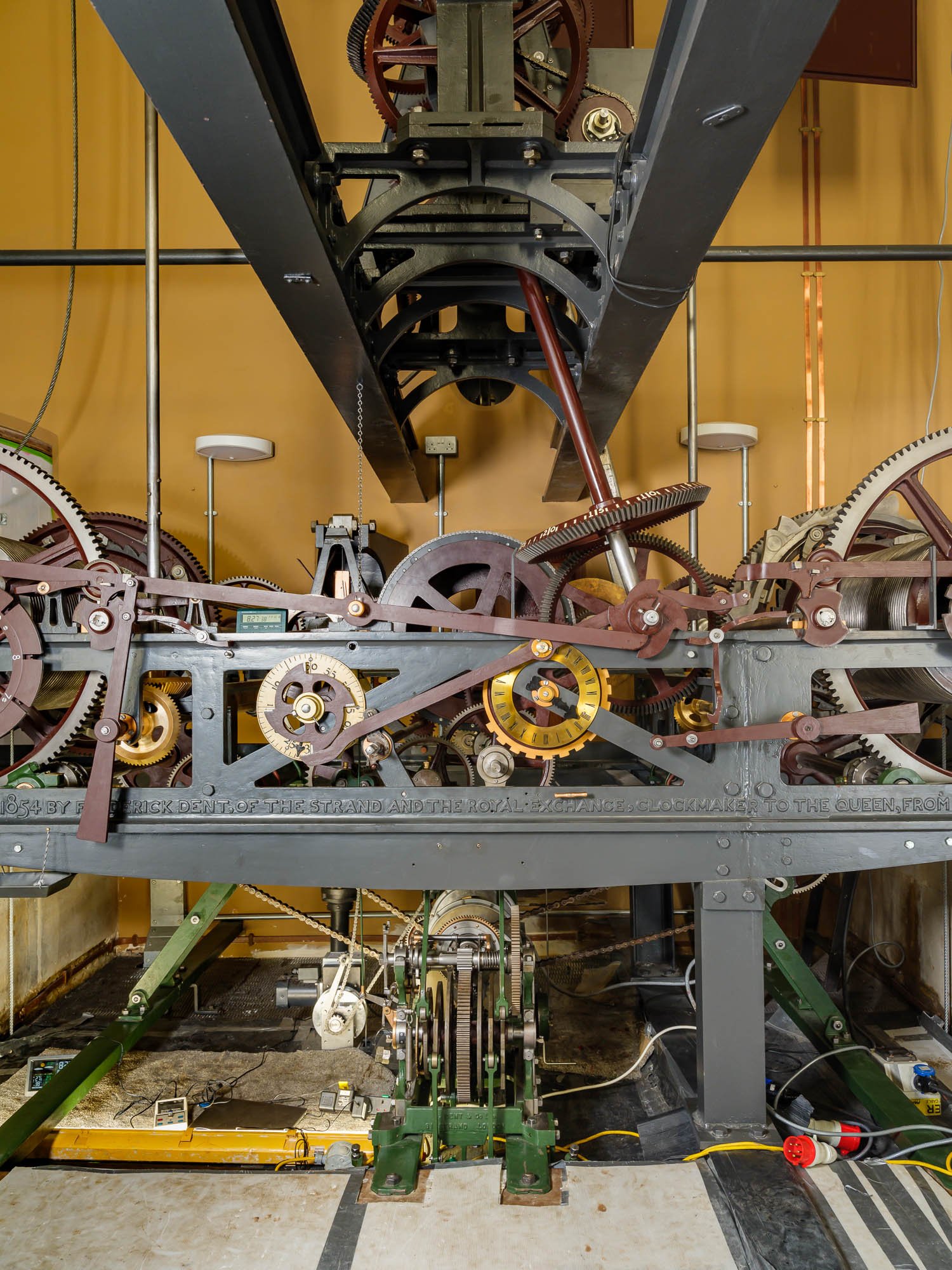

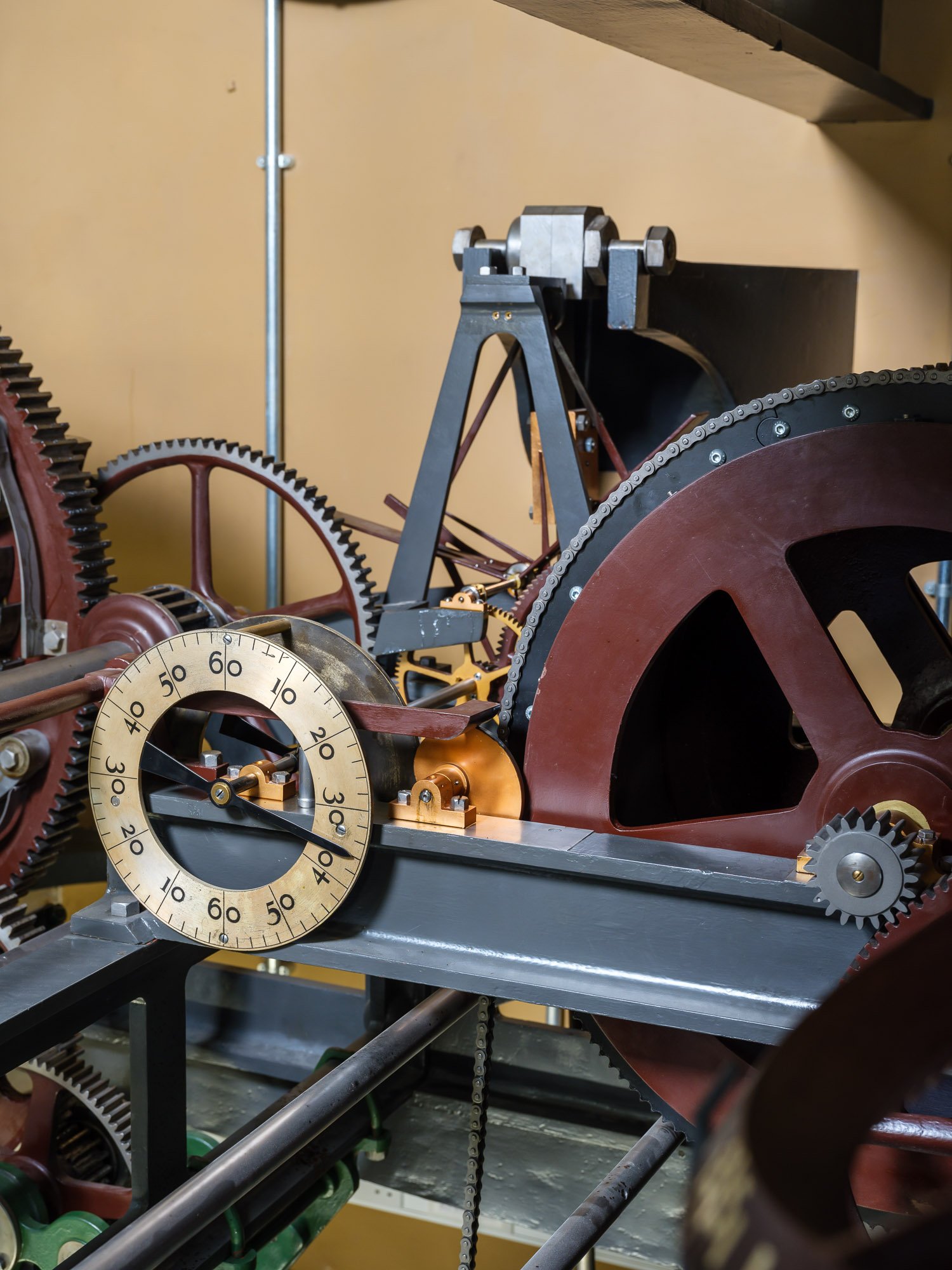

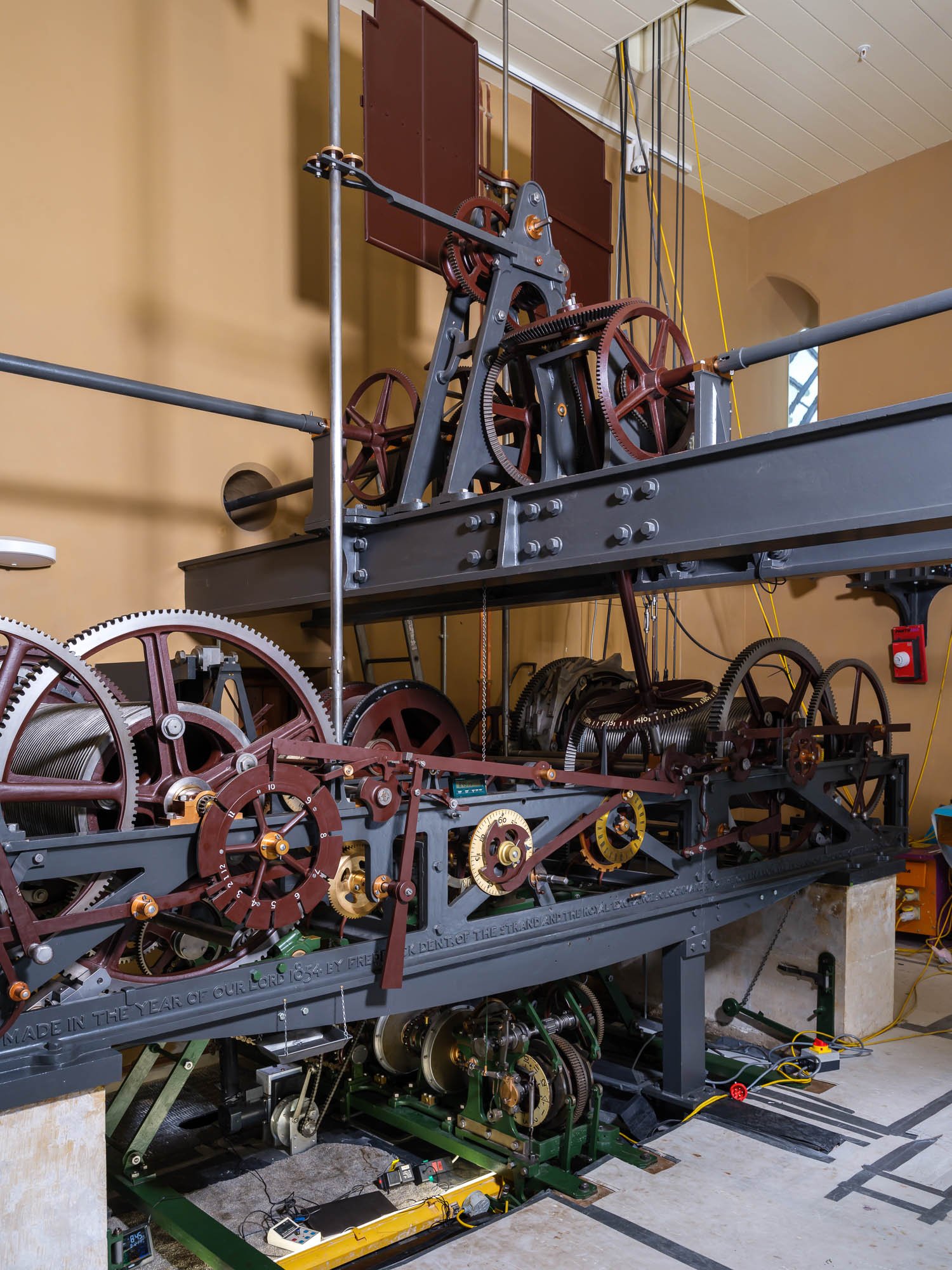

It will be. But not before 13.5 tonnes of iron and brass mechanics, including their drive weights, ropes, and a 170kg pendulum, as well as eight hours- and minutes-hands, have been reinstated.

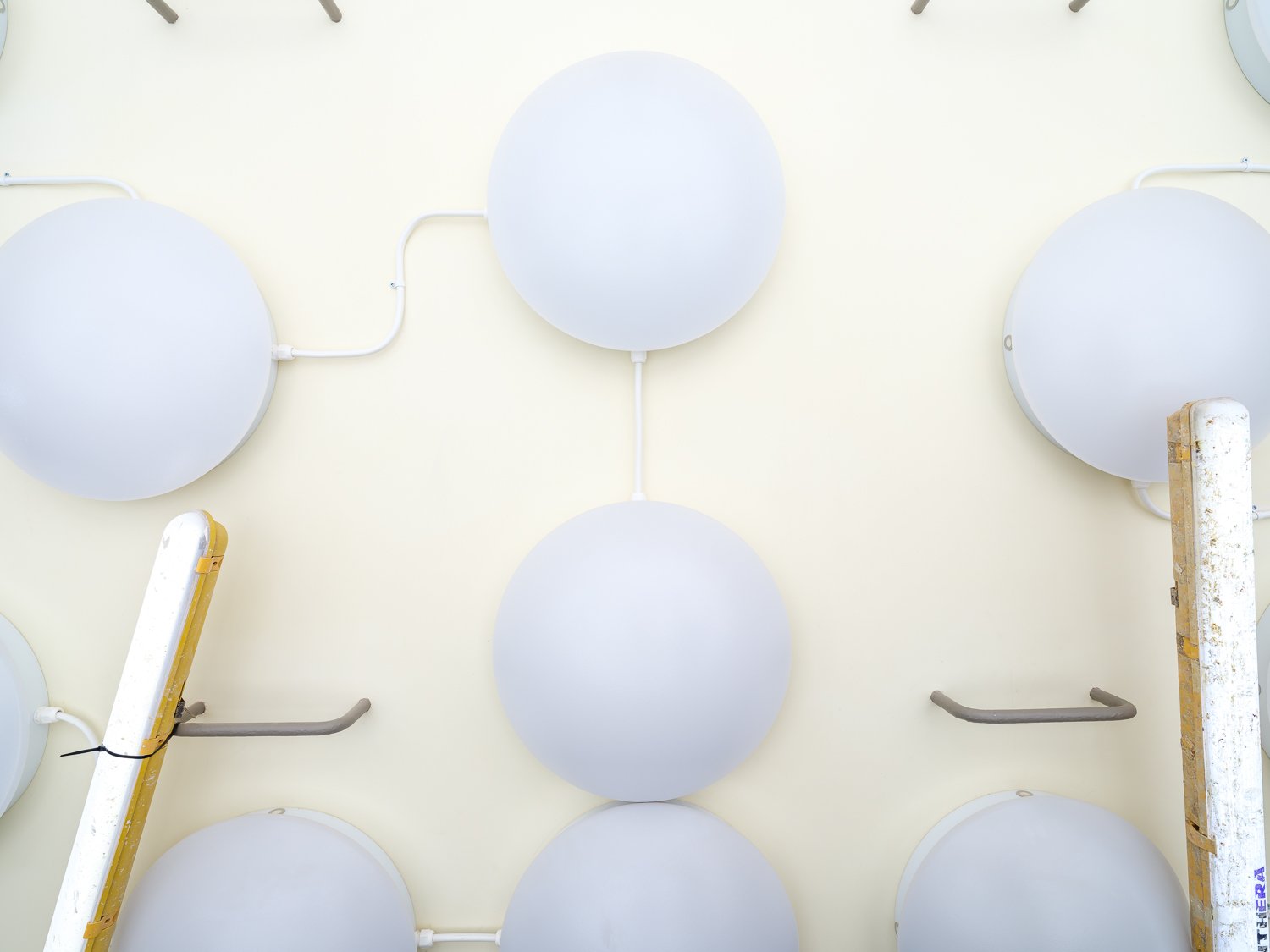

Repair work on Westminster’s Victorian, neo-Gothic icon started in 2017. Hundreds of specialists, from gilders to masons and glaziers, undertook the most complex conservation project in the tower’s history, after decades of stone-crumbling pollution and weather, previously undiscovered asbestos, and visitor groups traipsing those famous 334 steps (UK citizens can write to their local parliamentary representative to request a free tour). But for the clock itself, all 1,000 components took a holiday to Dacre, Penrith, some 270 miles north of London.

“We transplanted the ticking heart of the UK up to Cumbria,” says Keith Scobie-Youngs, director of the Cumbria Clock Company. “We were able to assemble the timekeeping core, and put that on test in our workshop, so for two years we had that heartbeat ticking away. It became part of the family, and its return to Parliament was like a child leaving home.”

He and his team at the Cumbria Clock Company’s workshops, deep in the Lake District National Park, were charged with the task of not only painstakingly cleaning, repairing and restoring the clock (all under the strictest secrecy, for fear of theft), but making detailed photos, notes and drawings, as neither the designer Edmund Beckett Denison nor manufacturer Edward John Dent did so back in 1859. The result is the first-ever user manual and set of engineering diagrams for “Big Ben”.

The work went well,” says Ian Westworth, who heads up the Palace of Westminster’s three-strong team of clock keepers, “because CCC are great, but also because the clockworks were incredibly well made in the first place. It’s Victorian engineering on steroids.”

As well as documenting the assembly itself, a large part of the work in Cumbria has been to adjust design flaws and retro-engineer features for easier servicing. Lubrication points have proven pivotal, shoring-up bearings that were hard to access in the past, such as those of the clock hammers. “We also invested in making lots of tools for easy ongoing maintenance,” Westworth reveals. “Milling-out new spanners to fit obscure nuts, for example. Or, on a bigger scale, a set of gear pullers to ease those 300- and 100-kilo hands from each of the four dials’ axial shafts. We fabricated a frame that sits behind the hands, mounted by two protruding arms on a thread that, when turned, gradually ‘pinch’ off the hands from their arbors.”

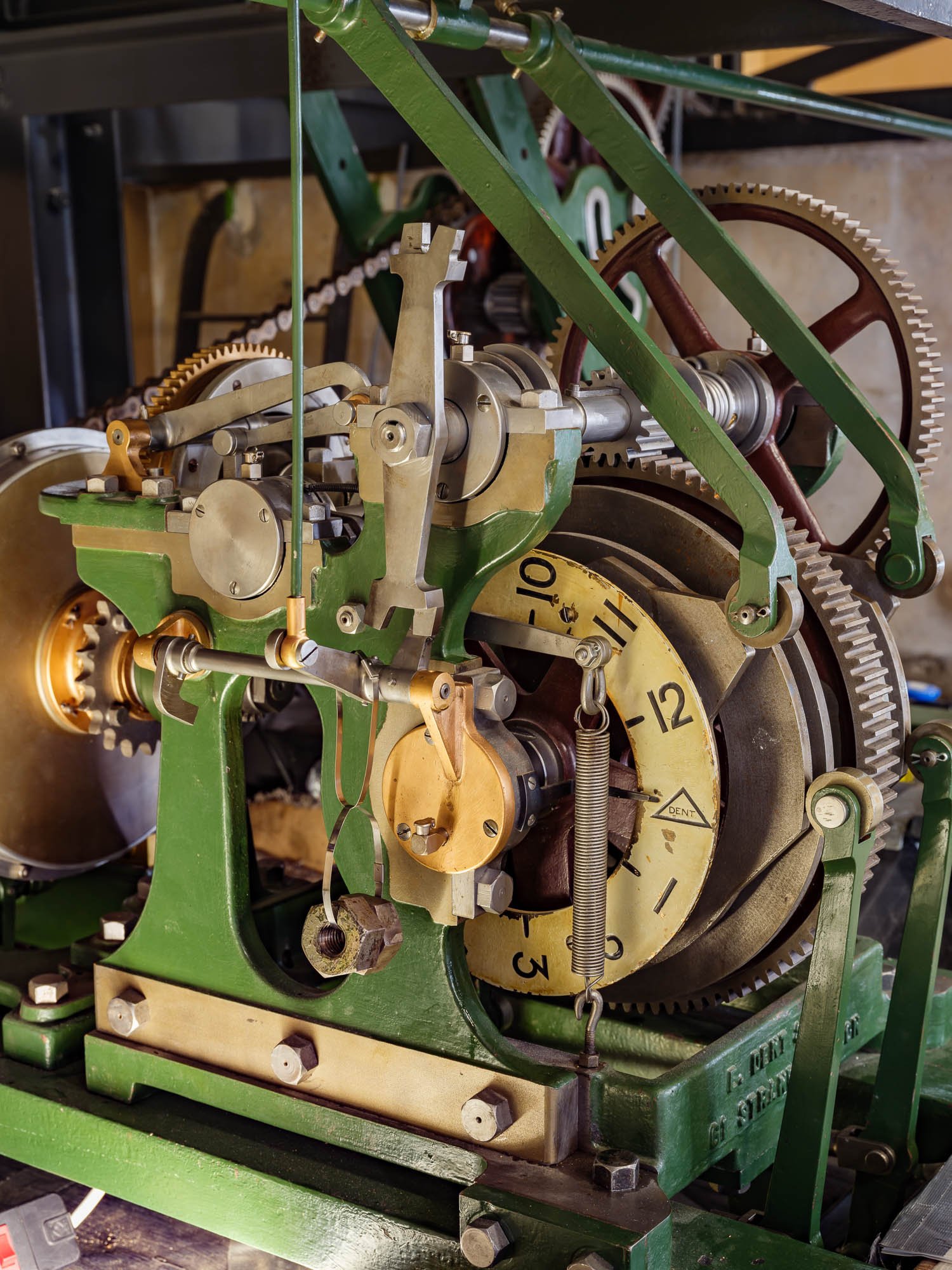

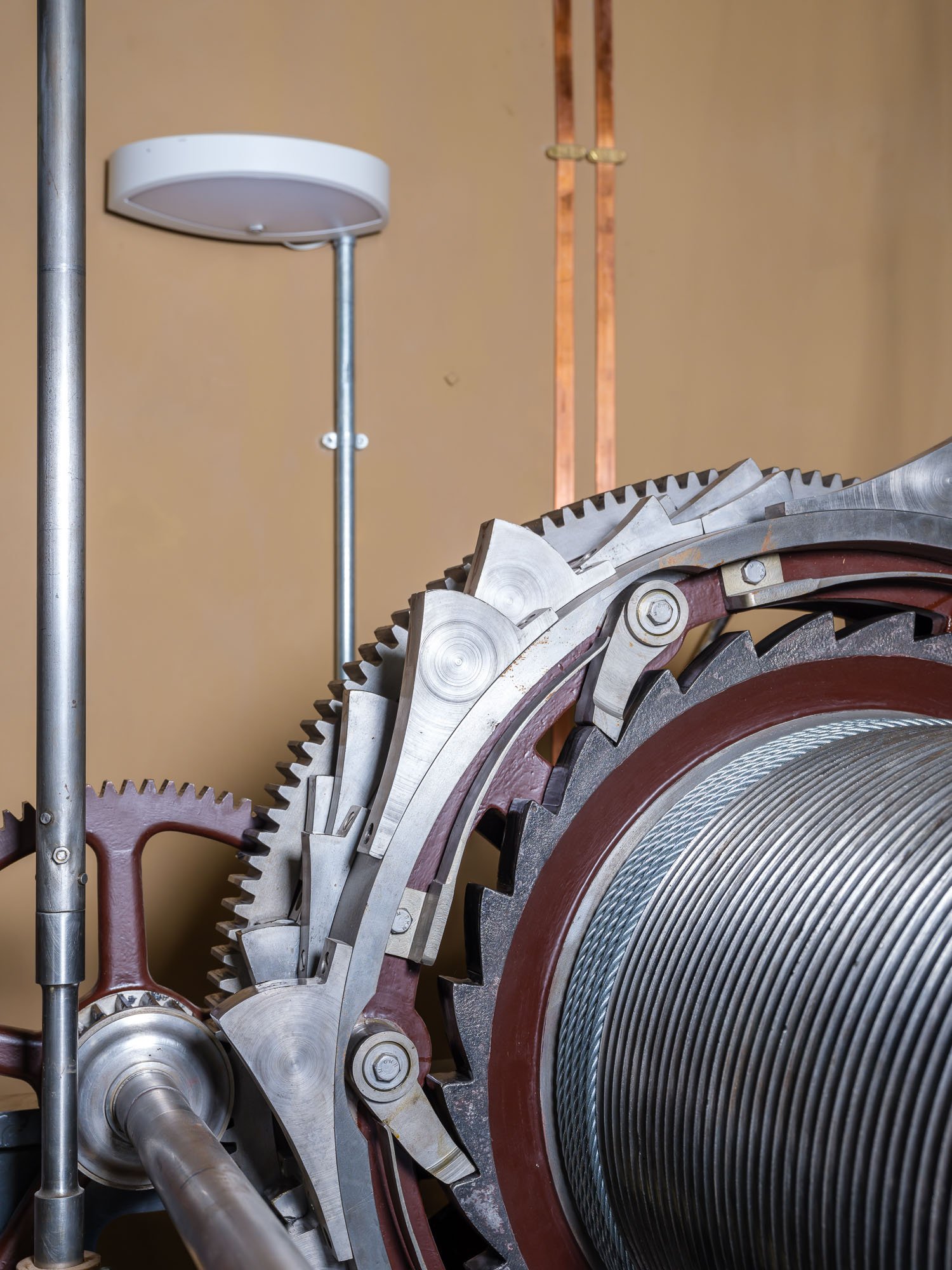

Big Ben’s mechanism was revolutionary for it being fitted with a “double three-legged gravity escapement”, which regulates the speed of the mechanism’s “tick” more steadily than anything before it. It “detaches” the impulse of the pendulum—its swing fine-tuned, famously, using old English pennies placed on top—from the escape wheel connected to the clock hands’ precisely ratio-ed geartrain. Thus, the pendulum is kept in motion by an utterly consistent pulse (powered by weights hanging the length of the tower), unaffected by wind, rain or snow swirling about outside.

“It’s been a huge privilege to follow in the footsteps of the greats and become part of its story,” says Scobie-Youngs, who established the UK’s leading turret-clock maintenance firm in 1990, and counts the country’s oldest (that of Salisbury Cathedral) among its wards. “All clocks absorb their makers, they say. Not least John Vernon, the chap who first ventured up the Elizabeth Tower in 1976, when metal fatigue had caused the tightly loaded mechanism to literally explode, taking chunks out of the interior masonry. In fact, without John, we wouldn’t be doing what we’re doing, thanks to his singlehanded repair work. We even discovered his name scratched on the weights.”

Scobie-Youngs, Westworth et al. found that getting into the head of Dent and Grimthorpe proved as important as the metalwork. Besides Vernon’s 1976 notes, they had an 1860 edition of A Rudimentary Treatise on Clocks, Watches and Bells for Public Purposes, which Grimthorpe had updated with an 18-page chapter on “The Westminster clock”, just one year young.

“Sitting and reading it up in the Tower,” Scobie-Youngs recalls, “I realized Vernon only had a front elevation of the geartrain [the meshed cogs forming the core clockwork] to go on, illustrated for the frontispiece. Before turret clocks were industrialized with the advent of standardized GMT, clockmakers just did the gear ratios, then built the mechanism as they went along. As a result of disassembling the entire mechanism for the very first time, we’ve taken the opportunity to create a full suite of 3D CAD drawings, working with my brother Rob, whose company Tempus Consulting is usually in the business of robotics and motor drives. Thanks to him, there’ll be no doubt whatsoever for the next generation of palace clock-keepers.”

Naturally, this 3D modeling proved to be a whole new world to a certain breed of artisan more used to an anachronistic approach. But now, every elevation of every major component has been drawn up on a traditional drawing board, then entered into a CAD program (Tempus uses Autodesk’s Inventor), and rendered as 3D files. “It’s afforded us a fresh perspective on the mechanics buried deep inside. The ability to rotate in all angles means any faults occurring in the future will be easier to diagnose,” says Scobie-Youngs.

So, if you’re planning on visiting Westminster from October 2022, rest assured: you’ll be able trust all four dials to set your watch, more than ever.