After moving house four times in one year, and lugging my 800 strong vinly record collection with me every time, I decided enough was enough. Seriously, have you ever tried lifting moving boxes full of records up and down three flights of stairs? It is rubbish. So I decided it was time to make a cull, and got the guy from the local record shop to come round and spend a whole night going through them while I plied him with beer and joints. In the end he offered me an amount of money that nearly made me cry: the hours I had spent looking for those records, digging around in charity shops in obscure eastern European countries, lugging them up and down those bloody staircases, and this is what I get for it. Peanuts. I took it, and was very happy about it next time I moved apartment.

But I'm not a complete idiot, I did save a couple of hundred of my favourite ones, and like many others I recently dug them out and hooked up the record player, and have been bopping away to those glorious analogue sounds for the last few months. As someone that dedicated many teenage and twentysomething years to the love of vinyl, going for a trip to the largest pressing plant in the world was a spiritual journey. Vinyl is back on track.

Shot for N by Norwegian magazine, August 2015.

Words by Toby Skinner

The Haarlem Shake-Up

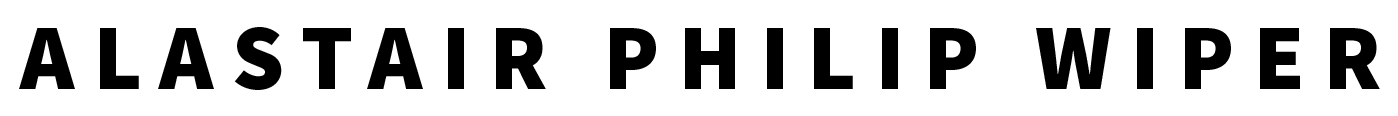

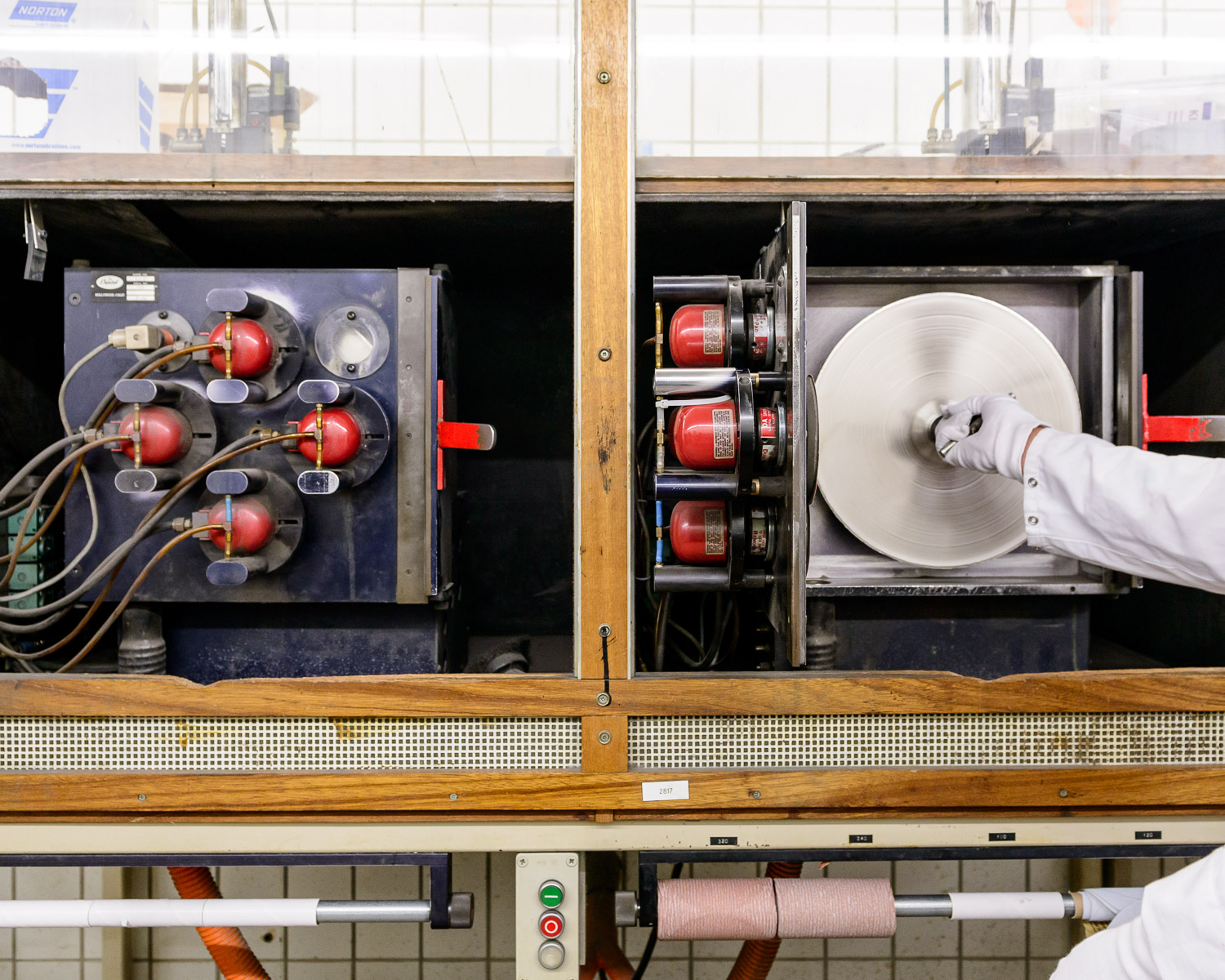

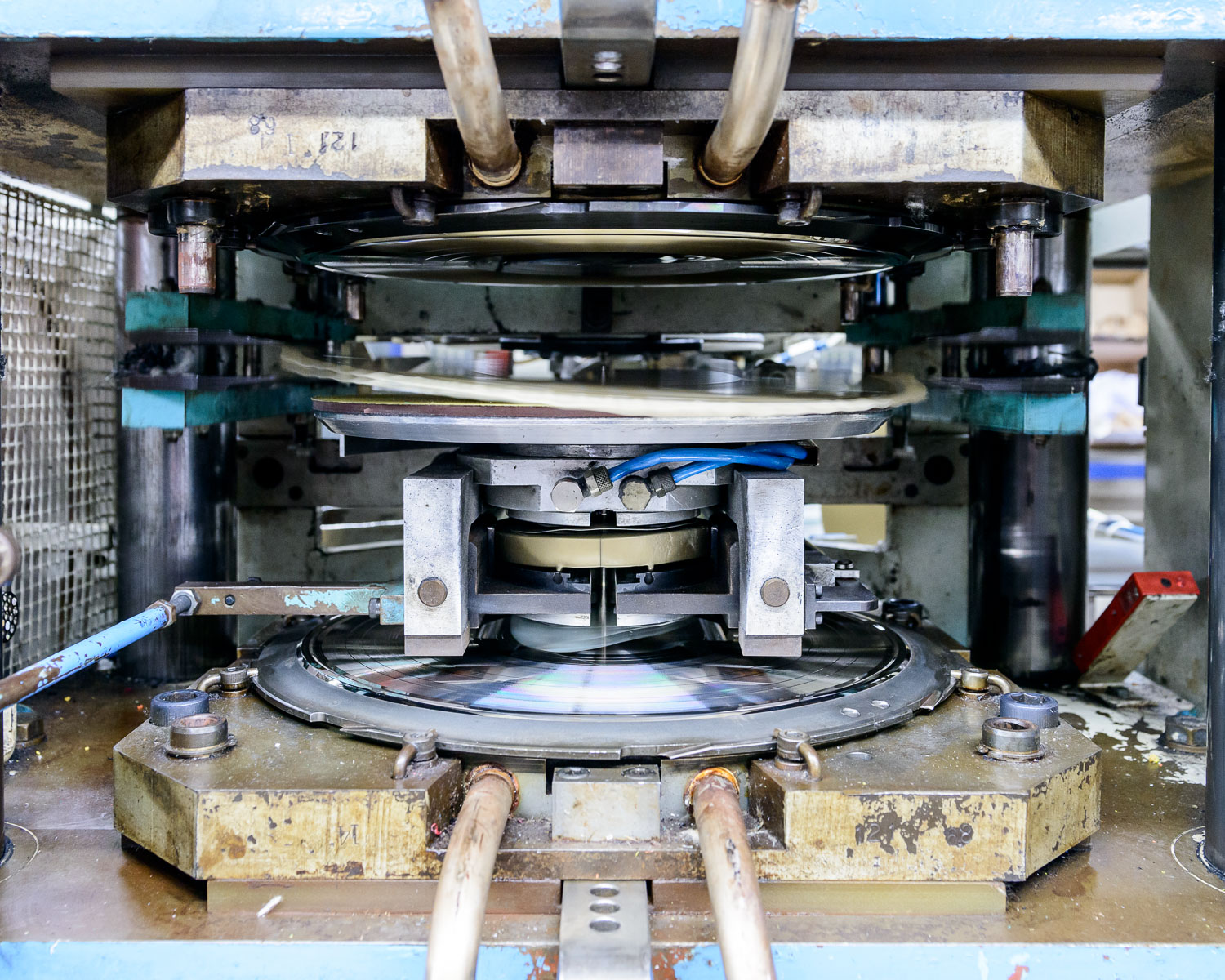

In the industrial quarter of Haarlem, not far from Amsterdam Schiphol airport, is a scene that was no longer meant to exist. Machines are clicking, clacking and whirring, just about drowning out the dance music that’s playing on the radio at ear-splitting volumes. Made mostly in the 1980s, the machines are lacquering, cutting, washing, stamping, labelling and boxing vinyl records.

This is Record Industry, a 6,500 m2 factory building which claims to be the largest vinyl pressing plant in the world, with 33 presses. It’s one of very few that can handle the entire process of creating a vinyl record, from cutting copper and lacquer masters to printing sleeves.

And times are good again. “It’s actually too good,” says the factory’s owner, Ton Vermeulen, a former DJ who was running a series of Dutch dance labels when he boughtSony’s last vinyl plant in 1998.

“Demand is sky-high and we’re having to turn people away, which I don’t like doing.” Since 2010, Record Industry has gone from producing 2.8 million records a year to a projected 7.5 million records this year, as worldwide vinyl sales have grown from less than US$40 million in 2006 to US$218 million in 2013.

Galvanic baths for development of metal parts

They’ve hired almost 40 new staff in the past few months and added a whole extra shift to meet a demand for records that Vermeulen admits “has taken us a little by surprise”. The medium that was meant to have died a quiet analogue death is cautiously thriving again.

It’s a far cry from just five years ago, when the plant had to lay off 12 people and was losing money. “We were constantly thinking: will we still be here next year?” remembers Vermeulen. “We were desperately thinking of new ways to make money, because the final death of vinyl seemed inevitable.”

Record Industry started life here as a vinyl plant called Artone, founded in 1958 by Belgian oil trader Dirk Slinger, who started making seven-inch records. When CBS, an arm of Columbia Records, bought a 50 per cent share of Artone in 1966, they started printing their own sleeves, starting with Nancy Sinatra’s Like I Do (it bombed Stateside but reached number two in Italy).

Columbia took over full ownershipn of the plant in 1969, in time for the vinyl boom of the 1970s and early 80s, when the album was king and the music industry became bigger than Hollywood. By the mid-Seventies, Haarlem was pressing 50 million records a year; in the 80s, the plant pressed more than 40 million copies of Michael Jackson’s Thriller alone. By the time Columbia merged its catalogue with Sony in 1988, the Haarlem plant was the most important in Europe.

But CDs had already overtaken vinyl as the primary way the world listened to music and, by 1998, the big labels wanted out. “They didn’t see any future for it and were busy getting rid of physical formats to focus more on managing rights,” says Vermeulen, who at the time was getting many of his dance records pressed at Haarlem’s Sony plant. Vermeulen had no experience of running a factory, but saw an opportunity. “For a start we were in dance music, and DJs were still all using vinyl. But I also felt that this was a format that would never fully disappear.”

He bought the Sony plant in 1998, renamed it Record Industry, and at first things went well. Dance music was dominant, making up 90 per cent of Record Industry’s records; and when EMI closed their vinyl operations in the UK, a slice of their production went straight to Haarlem. In 2001, they pressed 7.8 million records.

But the signs of decline were there. In 2001, The Strokes released Is This It, signalling the return of guitar music in the same year that Steve Jobs launched Apple’s iTunes and later the iPod. Trance – which had been a key part of the business in the years of Dutch superstar DJs like Armin van Buuren and Ferry Corsten – went out of fashion, and laptops started replacing turntables in DJ booths. In the Noughties, as both independent and chain record stores closed at a rapid rate, vinyl was in trouble.

By 2010, production at the Record Industry plant had fallen to just 2.8 million records. “We were laying people off, cutting work hours and looking at other ways to make money,” says Vermeulen. “It was bad, and we were really questioning whether we should keep going.”

But they did, and in 2011, “things started picking up”. According to Anouk Rijnders, the sales manager at Record Industry, the revival started in the US. “Suddenly, and it’s hard to know exactly why it happened, youngsters started wanting to buy albums and discovering vinyl all over again. It was maybe just a natural result of the digital age – people wanted to own a thing again; they wanted a possession with emotional value that they could touch and hold.” The trend has continued, helped by initiatives such as the annual Record Store Day, and this year is set to see more growth in the global industry – at Record Industry, they’re predicting that they’ll produce 7.5 million records this year.

Still, rather than being seen as a relic, vinyl records have become a signifier of legitimacy, and it is CDs that seem to be heading for the garbage can of history. “If you’re a proper musician and you play with a band, you want to release your records on vinyl now,” says Vermeulen. “It’s become a sign that you’re the real deal as an artist, and for youngsters it’s become a sign that you’re a real fan.”

Today, he says, the types of records they’re pressing has changed. Whereas dance music made up 90 per cent of the output in the early days, today it’s less than a fifth. Around half of the music pressed at Record Industry now is new music from the likes of Ed Sheeran or Lady Gaga; the other half is made up of re-issues of old classics. The most pressed record of the Record Industry era has been the 30-year anniversary LP of Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon, which has been pressed more than 100,000 times. It doesn’t exactly compare with Thriller, but then Vermeulen points out that “the days of artists selling millions and millions of albums, on whatever format, has gone.”

“A lot of it will be about labels going through their back catalogues,” says Vermeulen, who admits that he’s not a Pink Floyd fan. “I’m still an old raver, really – I think you always get caught up on the music you were listening to from 16-25. My wife likes the Beatles and Pink Floyd, but I’ll still go and see Nile Rodgers at [famed Amsterdam club] The Paradiso.”

While Vermeulen goes and listens to his old vinyl records a few times a month, he says that his 90 or so factory workers aren’t vinyl nerds. “I don’t want that at all, actually,” he says. “I don’t want people nicking records, and I want them to focus on producing a quality product, rather than getting hung up on the music. The people here are real professionals.”

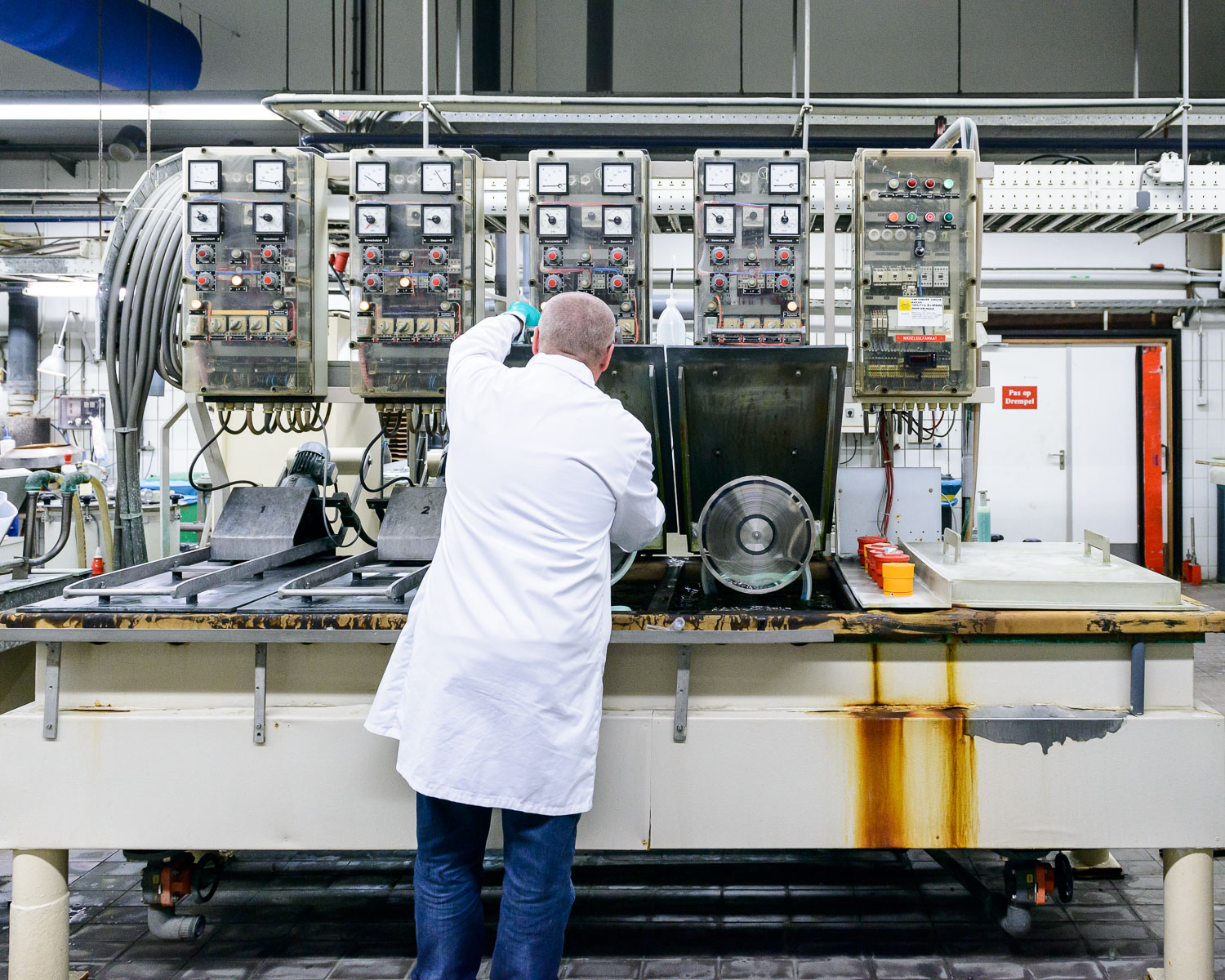

Fittingly for an old industry, the machinery at the Record Industry plant is mostly from the late 1970s and 80s. Despite rising demand, there hasn’t yet been enough an explosion to compel companies to invest in new technologies.

“The process hasn’t really changed – we still make records with moulds and steam, on the same machines that pressed Michael Jackson records,” says Vermeulen.

What they are doing is using new software programmes trying to speed up and refine the process, and they’re in the process of adding 10 or 12 presses to meet the rising demand. Whereas five years they were touting around for business, today you have to book a slot months in advance and often wait 10-12 weeks for a finished product. “One of the biggest issues we have now is keeping labels happy,” says Vermeulen, “because now they’re having to join the queue.”

Cutting the first master from copper

If there’s perhaps a wider issue of how an industry that is mostly run by passionate private owners adapts to rising demand, Vermeulen is happy with his lot. “I’m not worried about the next three or four years,” he says, “but you never know what can happen. Hopefully we can grow to press 10 or 12 million records a year, but I want to make sure that quality is always first and foremost.”

As for whether he is a visionary who saw the vinyl revival coming back, he’s unequivocal. “That’s total crap. There were quite a few times when we should have got out of this, but I just loved the product and could never quite see a world without vinyl records.”

Recordindustry.com