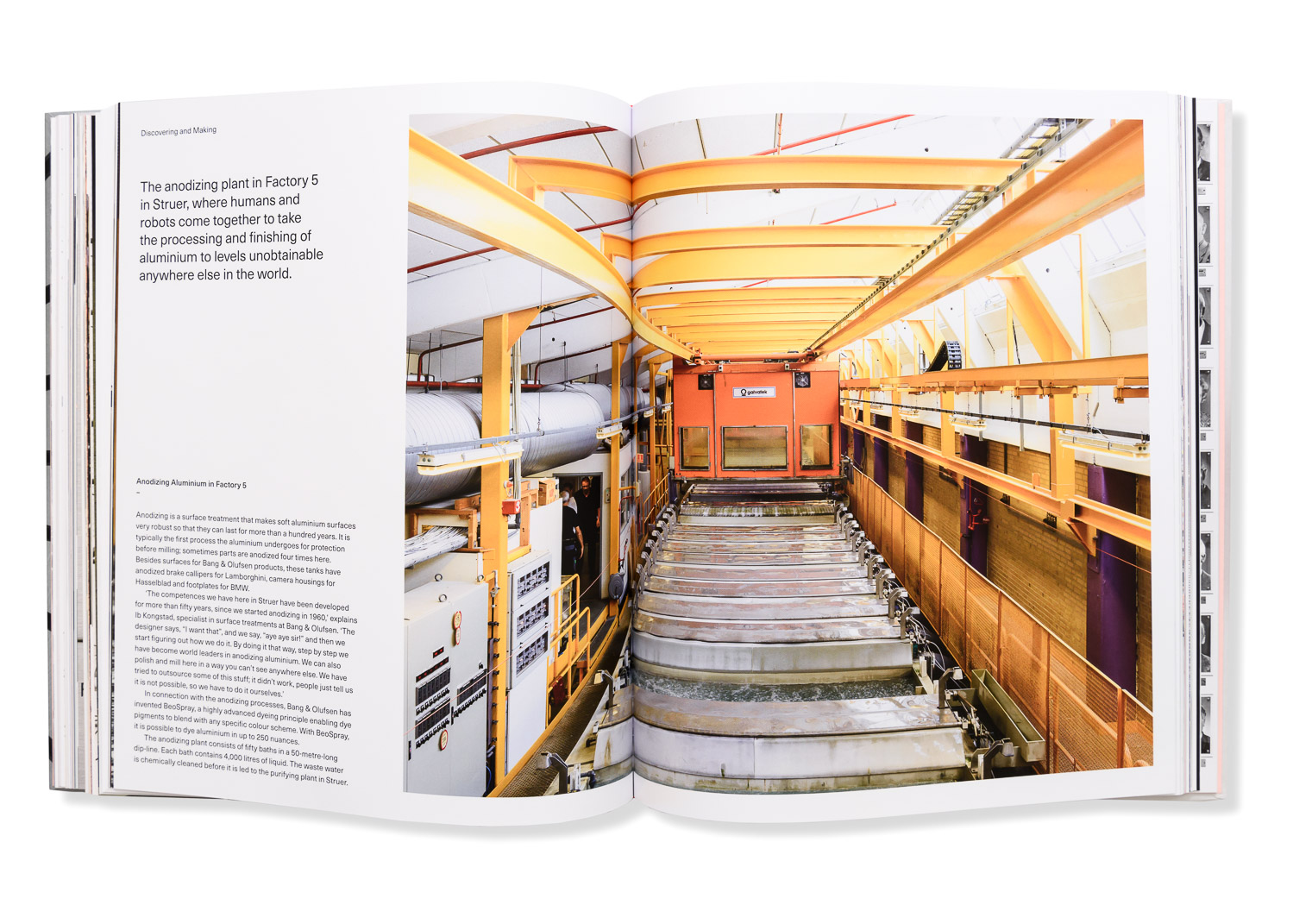

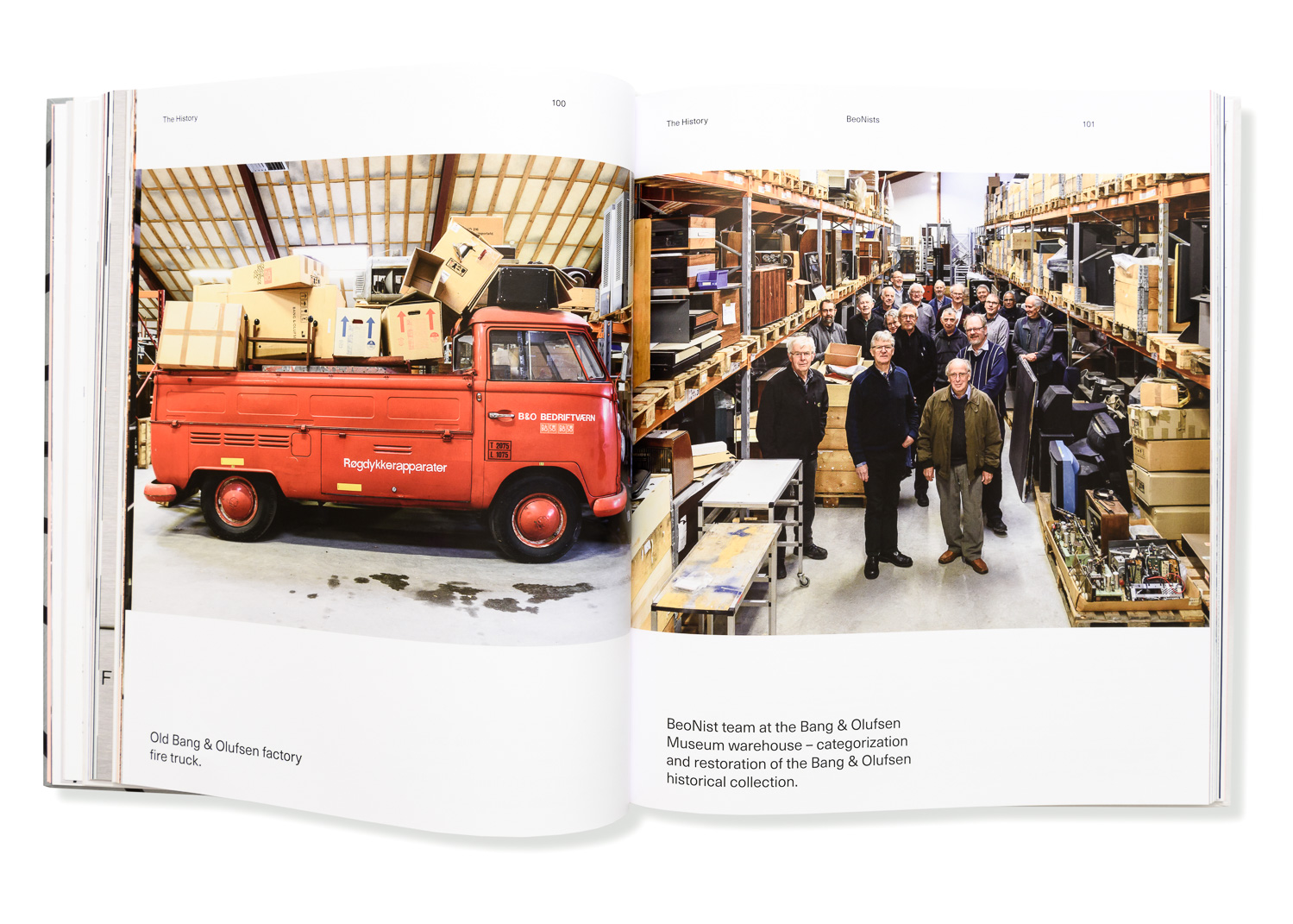

I'm very proud to announce the release of my new book, The Art of Impossible: The Bang & Olufsen Design Story, published by Thames & Hudson. Coming to a bookstore near you, with 240 pages photographed and written by yours truly and designed by the amazing Claus Due of Designbolaget, the book is an exploration of the oldest consumer electronics company in the world, which turns 90 years old today. I've spent two years scouring the basements of their headquarters in Struer, Denmark, digging out old prototypes of classic designs, talking to designers old and new, visiting the R&D and production facilities and much more. Check out a review by the nice people over at Creative Review. And check out some pictures below. And then buy it here!

Scroll down for an extract from the book's intro, to give you all a little taster ...

Introduction: The Bumble Bee from Struer

–

You have probably never heard of Struer, let alone have any idea where it is. On the west coast of Jutland, four hours’ drive from Copenhagen, it is the home of Bang & Olufsen, the oldest consumer electronics company in the world.

Like many Danish companies, Bang & Olufsen is fuelled by litre upon litre of black filter coffee, but the coffee at Bang & Olufsen must have something special in it. On my visits to Struer I have come to warmly anticipate the ceremony at the beginning of an interview when my host asks eagerly if we shouldn’t have a cup of coffee, while someone tries to find me the portion of UHT milk they thought they saw at the back of a cupboard a few months ago. I gave up on the milk early on and embraced the black stuff.

This book is the culmination of my experiences exploring the ins, outs, ups, downs, fronts and behinds of an eccentric and visionary company that has taken design and technology to unparalleled heights. Two and a half years ago I first pitched the idea of this book to Bang & Olufsen, and they have run with it all the way. No subject has been off limits, and I was given an unprecedented amount of freedom to research, photograph, interview and write about what goes on behind the scenes. This is not a polished marketing book and was not intended to be; it is an honest insight into the daily life of a special workplace. It should surprise you, inspire you, and make you smile.

‘It’s like the old theory about the bumble bee that shouldn’t be able to fly, but it does anyway,’ says Torsten Valeur, who is one of the many designers who have worked with Bang & Olufsen over the years. What Torsten means is that this small company in the outback of Denmark, among the farms and fjords, should not be able to compete with the big boys; and yet for ninety years a group of proud and dedicated specialists in Struer has been giving the world a lesson about what innovative design, superior technology and quality workmanship really mean. Elevating everyday products such as loudspeakers and telephones into objects that people develop emotional attachments to is no mean feat, and it is what has made Bang & Olufsen a brand unlike any other. The spirit of Struer has reached far and wide.

Generations

–

‘Oh no, not that bumble bee story again,’ says Iza Mikkelsen as we sit having lunch with her parents at the house she grew up in, a few hundred metres from the Bang & Olufsen factory in Struer. Iza is Product Communications Consultant at Bang & Olufsen, and she has been my guide during the making of this book: together we have scoured dusty basements for prototypes of old products, driven around Jutland in the rain, explored every corridor of the Bang & Olufsen facilities and visited the local pub, The Happy Penguin, more than a couple of times. A second-generation Bang & Olufsen employee and former competitive ballroom dancer, Iza has grown up in the company and knows everybody in Struer, greeting them as we are out and about with a cheeky smile and a chat about how their parents are doing.

During my first visit to Struer, Iza showed me the ‘Wall of Fame’ in the canteen of Factory 4, an epic 30-metre-long wall displaying the portrait of every Bang & Olufsen employee who has worked for the company for a period of at least twenty-five years; some even made it to a half-century. That wall became something of an inspiration for this book: there are an awe-inspiring 1,231 portraits on that wall. You can see them all on pages 226 to 239. Co-founder Peter Bang is the first portrait on the wall, but his partner Svend Olufsen didn’t make it as he died a few months before his twenty-fifth anniversary. Rules are rules.

Seeing this wall is a humbling experience. ‘The spirit that was created during the first twenty-five years of Bang & Olufsen’s life has survived until now,’ says Ronny Kaas, a third-generation Bang & Olufsen employee who has worked for the company since 1961, and who now serves as its history specialist. ‘You could talk about it like an organism that has carried its spirit with it. Those might sound like big words, but there really is a Bang & Olufsen spirit. And if you come with an open mind, there is always the possibility of being a part of Bang & Olufsen.’

The company began life in the attic of a manor house in Struer in 1925, started by two young engineers with a passion for radio and a keen eye for an opportunity: Svend Olufsen and Peter Bang. Apart from a few diversions, design at Bang & Olufsen wasn’t particularly radical for the first thirty years and they made products that looked pretty much similar to everybody else’s, focusing instead on technology and innovation. But in the mid-1950s something happened, and the Bang & Olufsen that we know today began to take shape.

‘There was an exhibition in Copenhagen in 1954 where the furniture industry in Denmark showed that there were new times coming,’ says Ronny Kaas. ‘The big architects like Arne Jacobsen and Hans Wegner were influencing all of the younger guys to be more daring, to reach for new shapes and new materials. Teak became very popular, colours began to be used more, and people began to change their home environments to be more cheerful and more happy.’

These new trends were shown to the public through exhibitions, and old-fashioned radio cabinets were put into the exhibitions because there were no alternatives. Those cabinets received a great deal of criticism for not moving with the times, and started a discussion about how radios should fit in with modern daily life. The most notable critic was the famous architect Poul Henningsen, who said: ‘It is an insult to people who value modern furniture to force them to buy these monstrosities in order to enjoy the considerable cultural asset embodied by the radio. Has this thing been designed by fishmongers or potato wholesalers with nothing better to do in their spare time?’

Heeding the criticism, a few radio manufacturers started to work with architects, Bang & Olufsen among them. After four years of research, in 1958 Bang & Olufsen started to change the way it did things and began the close collaboration with external designers that would come to define the company’s way of working. Architect Ib Fabiansen was one of the first to really instigate a new direction for the brand.

No Compromise

–

In the modern era Bang & Olufsen has worked only with external designers, and that collaboration has been an integral part of the success of the brand. ‘All Bang & Olufsen designs have a built-in story and idea – and when we have done our job really well, you should be able to understand what the idea is by looking at the design,’ says Marie Kristine Schmidt, Head of Brand, Design and Marketing. ‘We are not trying to create design that pleases everyone, but we make a huge effort to try and understand how our customers live at home, enabling us to make the right choices based on these insights.’

A look at the products of the last fifty years will reveal the work of many talented designers, including Ib Fabiansen, Acton Bjørn & Sigvard Bernadotte, Henrik Sørig Thomsen, Lone & Gideon Lindinger- Lowy, Anders Hermansen and Steve McGugan. But two designers stand out from that crowd, each of whom has had an enormous influence on the design of Bang & Olufsen: Jacob Jensen and David Lewis. The two young men worked for Bang & Olufsen designer Henning Moldenhawer in the early 1960s before leaving to set up their own design firms, and later returning to Bang & Olufsen. Between them they designed many of the products that have made the company famous, Jacob from the 1960s to the 1990s on the audio side and David from the 1960s to the 2010s on the video and speaker side. They had very different personalities, and frequently clashed: Jacob had a reputation for being hard and demanding but also party-loving and charming, while David was quiet and reserved, but equally strong-willed.

Jacob Jensen began working on some small projects in 1965, and in 1967 he designed Beolab 5000, which proved to be a milestone product for the company. Ronny Kaas explains: ‘Ten years later, he came with a demand like “I want a radio that is less than 7 cm high,” and the engineers said it was not possible as the transformer was 8 cm high. “I want it!” said Jensen. It was like that a lot with Jensen. He never tried to be popular, he stuck to his ideas and convictions. Anyway, he was right to work like that because suddenly they found out that they could use a different type of transformer and he got his 7-cm-high radio.’

In 1978, MoMA staged an exhibition of the entire Bang & Olufsen portfolio, entitled ‘Bang & Olufsen – Design for Sound by Designer Jacob Jensen’. J. Stewart Johnson, Curator of Design at MoMA, began his introduction to the exhibition with the following words:

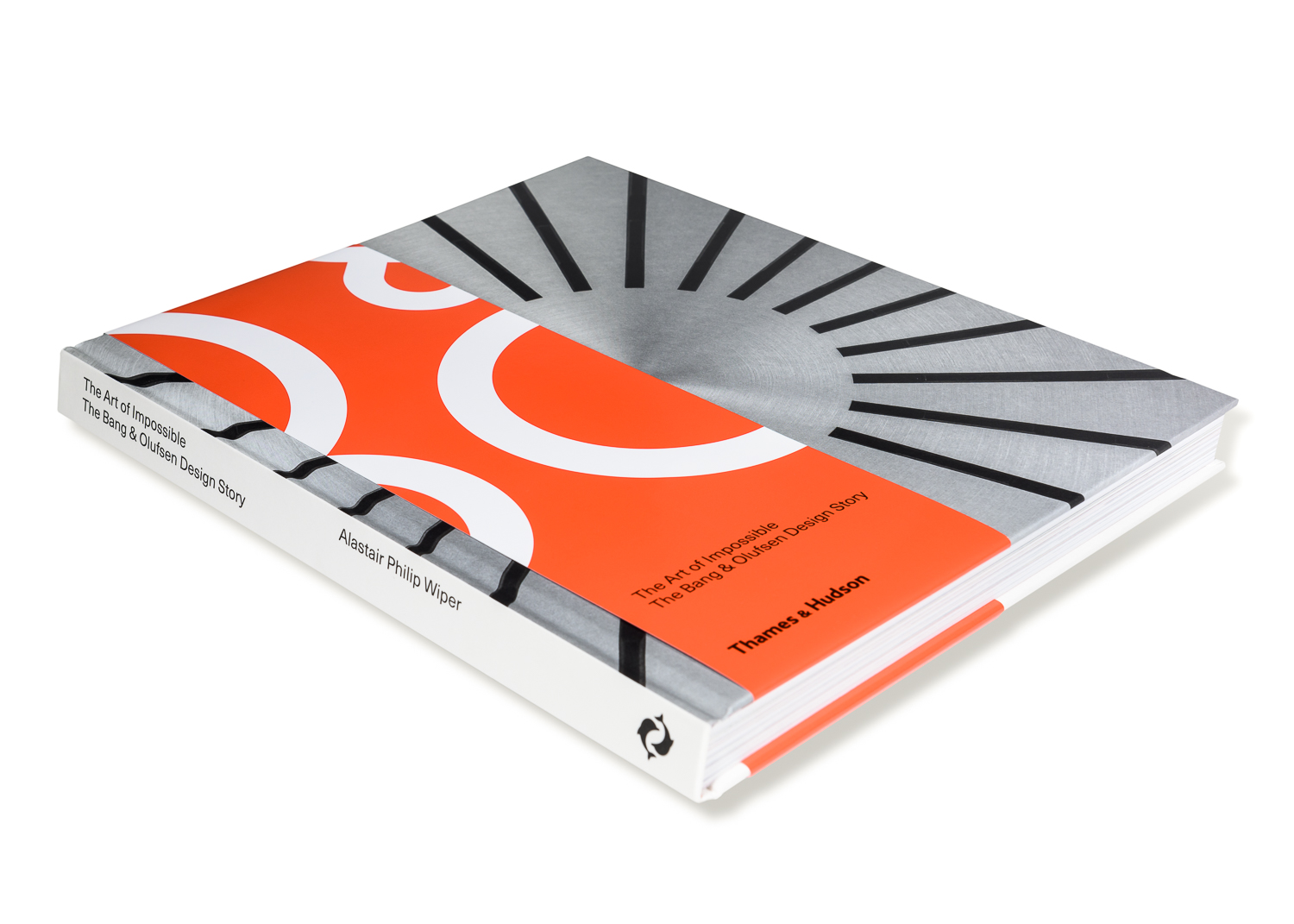

‘In seeking to domesticate sound equipment, Bang & Olufsen has visually de-emphasized the technical aspects of their components, making them virtual abstractions of the functions they are meant to perform. They are as well beautiful objects in their own right.’

Since that exhibition, several of David Lewis’s designs have also been acquired for the museum’s collection. Referred to by Peter Bang’s son Jens (head of R&D for many years) as ‘Bang & Olufsen’s best-kept secret’, David Lewis was, by all accounts, a very different character. A Londoner who met a Danish au pair in the 1960s and followed her to Denmark, David was a shy, softly spoken man, but was completely unwilling to accept compromise. Under David, the concept of movement and light was refined, as was the understanding that the products needed to stand out as beautiful objects, and blend in with the home environment at the same time.

Torsten Valeur took over David Lewis’s design studio after his death. ‘I know they had a good relationship at the beginning,’ he says of the relationship between David and Jacob. ‘Over the years their personal relationship deteriorated, but they could still work together and in a lot of ways I think they were a very good team because they both had different qualities that brought something to the company.’ Indeed, each in his own way, David and Jacob between them interpreted the spirit of Bang & Olufsen at exactly the right time.

Feeding the Engineers

–

The struggle between designers and engineers that traditionally besets technology companies was turned into a co-operation that has been vital for Bang & Olufsen, and designers of all eras have spoken affectionately of the engineers at Bang & Olufsen. ‘Good engineers are very open-minded,’ Øivind Slaatto tells me when I am photographing him in his studio in northwest Copenhagen. Øivind designed the BeoPlay A9 speaker in 2012. ‘At Bang & Olufsen the engineers are very open-minded. When you show a poor engineer something, they will just say “no, that is not possible.” They are idea killers. At Bang & Olufsen, the engineers are idea generators.’

Torsten Valeur agrees: ‘At Bang & Olufsen we can come with an idea that we know is impossible, but the engineers will feed off that and come up with something that no one has ever thought of before. With some of the engineers at Bang & Olufsen, I can sit with them and not have to say that much before they understand what my point is, where I am going with an idea. And then at the next meeting I will see that they have actually made my idea become reality, which is a wonderful thing. It is so different from other companies, where engineers come to meetings and just come with a list of problems.’

The flair for engineering and the desire to create high-quality products that was initiated by Peter and Svend in the early days have remained in the spirit of the company to this day, and have meant that throughout its history Bang & Olufsen has managed to attract talented and dedicated people to Struer, and keep them there. ‘At Bang & Olufsen they have some real nerds. And in my opinion, nerds are one of the best resources a company can have. I really like the nerds,’ says Øivind. Gert Munch started working for Bang & Olufsen in 1976, and when he is not selling his home-produced eggs from his desk he works as a specialist in electroacoustics.

‘I like the collaboration with designers. Sometimes they come with ideas that are just not possible, but we tell them what is possible and come up with other solutions, and after a lot of back and forth we have a product we all like. So the end product is better than what we started with, also in their eyes. We are all in the same boat, we want to get a marvellous product out of this, and you won’t get that by just sitting back and saying “no”. Of course we have “discussions”, but they are never unfriendly – we can’t bend the laws of physics, but we can find solutions and ways around them. That’s how we get the unique products; we want to make things that are not possible. That’s what we do every day, and why nobody else makes the unique products we do, because they give up way before us.’

Danish Blood

–

Bang & Olufsen runs through the veins of Danish society. ‘Every Dane has a piece of Bang & Olufsen inside them,’ says Cecilie Manz, who designed BeoPlay A2 and Beolit 12 for the company in recent years. ‘I remember the feeling of turning the button on a radio in my parents’ workshop, the quality was just so high and everything was so well thought through.’ As the pride of Danish technology and design, the company has shared its ups and downs with the nation throughout its history.

Bang & Olufsen stands for old-school quality, products that are built with pride by people who care, and that is a valuable yet hard- to-grasp concept for today’s society. On the one hand, educated consumers are crying out for a slowdown, for the world to return to a state where the things you purchase are important and add value to your life; and on the other they are looking for the newest technology every single day, meaning that the world is moving more quickly and disposably than ever before. Bang & Olufsen knows that doing things its own way has always been the key to its success, but that adaptation is also important.

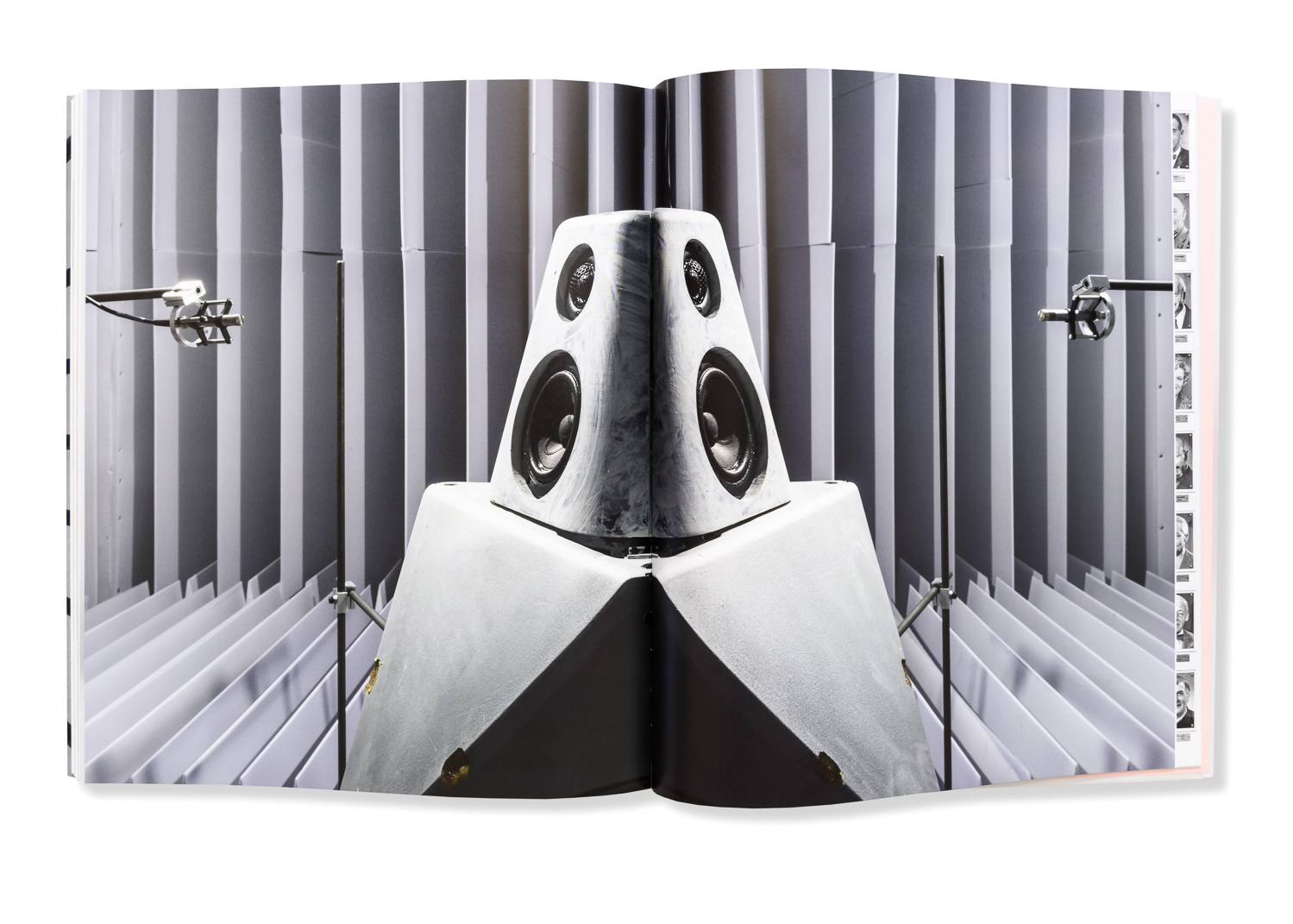

The ‘B&O PLAY’ brand was launched in 2012 to cater to a younger audience, producing high-end portable speakers and products that are more affordable than the main Bang & Olufsen line-up. This allows the core brand to concentrate on investing time and money in creating products that are completely uncompromising – and with its latest top-of-the-range speaker, BeoLab 90, Bang & Olufsen believes it is doing what it does best: creating audacious products that no one else would make. BeoLab 90 is an absolute monster, in the best sense of the word, and it is a statement: a rejection of the disposable and an elevation of design and quality over all else.

Connectivity is also one of Bang & Olufsen’s long-established strengths, and something that is important for its future as more and more devices are able to be controlled together in the modern home. Bang & Olufsen was the first company in the world to begin interconnecting its products in the 1980s with the BeoLink system; according to legend in 1992 Sony founder Akio Morita visited Bang & Olufsen’s stand at the World Exhibition in Seville and picked up a BeoLink 1000 remote control. Asked if he needed assistance, he replied, ‘Thank you, but I have one at home.’

The BeoLink system evolved steadily as more and more products became connectable, and today almost every controllable product you can imagine can be hooked up to the system and managed with just one Bang & Olufsen remote. Lights, curtains, coffee machines, air conditioning, security cameras – you name it, it can be hooked up to the BeoLink system and controlled through your Bang & Olufsen remote control.

The Sound of Struer

–

While working on this book I have built up a huge amount of affection for this unconventional West Jutland company: the people who work there do care. They care about creating the best products, they care about each other, and they care about the customers who are going to live with those products. I know it sounds ridiculous in this day and age, but it is true. Bang & Olufsen wears its heart on its sleeve with nothing to hide, and this book is the proof of that.

On one visit to the archives in Struer I stumbled across something that instantly brought back a flood of feelings from my childhood: the Beovision Control Module. The Beovision Video Terminal was the advanced remote control that was supplied with many of the Bang & Olufsen televisions of the late 1970s and 1980s, and my granddad had one as an accessory to the pride and joy of his life, his Beovision TV. Harry Wiper was a biscuit salesman from Yorkshire, and buying expensive luxury items was not his style – he even kept the plastic wrapping on the seats of his Honda so that it would retain its value when he sold it. But the plastic wrapping came off the Beovision remote control, and seeing the picture of that remote triggered memories that had long been buried at the back of my mind – I can still feel the cool metal of the remote and the reassuring (perhaps lethal) weight of the thing. Now I realize the amount of effort that went into making sure I would have these feelings twenty-five years later.

On my last day in Struer I decided that I needed to revive my vinyl collection, and what better way to do it than by bringing a Beogram record player back to Copenhagen from its spiritual home. So Iza took me to meet Viggo Kristensen of Bremdal Radio on the outskirts of Struer. Viggo opened his shop as a Bang & Olufsen dealer in 1978, and now he and his son run two departments next door to each other: one selling new Bang & Olufsen products and one selling old Bang & Olufsen products. Viggo gave us a tour of the fifty-odd record players he had in stock. My eyes fell on a white Beogram 1900 designed by Jacob Jensen in 1976, and after a demo and lengthy explanation about how to care for this marvel of the analogue age,

I was on my way with my piece of history under my arm. Rest assured that this book has been put together with the spirit of Struer playing in the background.

Here’s to the next ninety years.